“I can’t afford it.”

Four words that end more sales conversations than any competitor ever could. And in most cases, they’re a lie. Not a malicious lie — a protective one. The prospect sitting across from you, or hovering over your checkout button, has the money. What they don’t have is certainty.

Gary Halbert put it bluntly: “If someone wants what you’re selling, the thing that stands in their way is fear. And if you remove the fear, they will buy.”

Most business owners hear this and nod along. Then they go right back to tweaking their pricing, stacking bonuses, and writing “limited time only” across everything. They treat the offer like a math problem — pile enough value on one side of the equation and eventually the prospect tips over into buying.

It doesn’t work that way. And here’s why.

Desire is not the problem you think it is

When someone lands on your page, clicks your ad, or sits through your pitch, they already want what you’re selling. That part’s done. They self-selected. Nobody schedules a call with a financial planner because they’re happy with their current setup. Nobody searches “best CRM for small teams” out of idle curiosity.

You’ve probably felt this yourself. Think about the last time you almost bought something online — hovered over the button, maybe even entered your card details — and backed out. Were you lacking desire? No. You wanted the thing. You just didn’t trust the outcome.

That distinction changes everything about how you build an offer.

Most offers are designed to amplify desire. More features, more bonuses, more urgency. But your prospect already wants it. What they need isn’t a bigger pile of stuff. What they need is less risk.

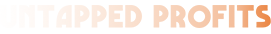

The three fears that kill the sale

Fear in a buying decision isn’t abstract. It takes three very specific forms, and each one demands a different response.

Fear of wasted money. This is the surface-level objection, and it’s the one most businesses fixate on. Payment plans, discounts, “just $3.27 a day” reframes — all aimed at making the money feel smaller. These help, but they only address the symptom.

Fear of wasted time. Deeper than money. Your prospect has tried things before. They’ve bought courses they didn’t finish, hired agencies that underdelivered, purchased software they abandoned after two weeks. Every new purchase carries the ghost of every previous failed attempt. When they say “I need to think about it,” what they often mean is “I don’t have the energy to be disappointed again.”

Fear of looking foolish. The deepest layer, and the one almost nobody addresses. Your prospect imagines buying your thing, having it not work, and then facing their partner, their team, or their own reflection in the mirror. The internal monologue: “You fell for it again.” This fear has nothing to do with you or your product. It’s entirely about their identity. And it’s the most powerful of the three.

Here’s what makes this tricky — a discount addresses fear number one but does nothing for fears two and three. A bonus addresses none of them. A countdown timer actually makes fear number three worse, because it pressures people into a decision they haven’t resolved emotionally.

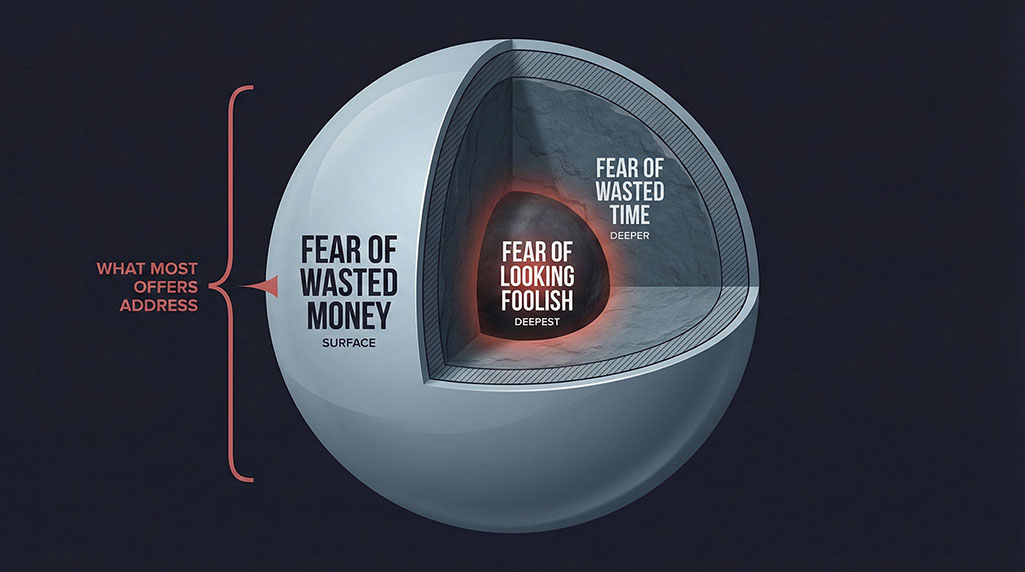

The fear removal framework

If the job of your offer is to dismantle fear, then every element of that offer should map to a specific fear.

For wasted money: Risk reversal. Not a buried refund policy in 8-point font — a guarantee so bold it makes you uncomfortable. “If you don’t see results in 90 days, I’ll refund every cent and pay for a competitor to fix it.” That sounds extreme. It’s supposed to. A guarantee that doesn’t make you nervous isn’t strong enough to make your prospect confident.

The maths usually works in your favour. When Zappos introduced their 365-day return policy, their return rate barely shifted — but their conversion rate climbed because the fear of being stuck with unwanted shoes disappeared entirely.

For wasted time: Demonstration, not description. Show the prospect what the first 48 hours look like. Not vague promises about transformation — a specific, tangible picture of what happens on day one, day two, day seven. When a carpet cleaner offers to clean one room free, they’re not giving away a service. They’re collapsing the time between “I hope this works” and “I can see this works.” The fear of wasted time evaporates the moment someone can experience the result instead of imagining it.

For looking foolish: Social proof with specificity. Not “trusted by thousands of happy customers” — that’s wallpaper. What works is a story from someone who was in the exact same position as your prospect, felt the exact same hesitation, and came out the other side. The more specific the proof, the more the prospect can see themselves in it. One detailed testimonial from a person who almost didn’t buy outperforms fifty five-star ratings, because it speaks directly to the fear of making a bad decision.

"This sounds like manipulation"

Right about now, something might be itching at the back of your mind. Aren’t you just exploiting people’s fears to sell them stuff? Isn’t this the same bag of tricks every sleazy marketer uses — just dressed up in psychological language?

Fair objection. And if you’re using fear removal to compensate for a product that doesn’t work, then yes — that’s exactly what it is.

But consider the alternative. Your prospect has a genuine problem. You have a genuine solution. The only thing standing between them and the outcome they want is a fear that you can address but haven’t bothered to. That’s not manipulation. That’s negligence.

A surgeon doesn’t manipulate a patient by explaining the procedure, showing the success rates, and offering to answer questions. They’re removing the fear that stands between the patient and the operation they need. Your offer does the same thing — or it should.

The difference between manipulation and service comes down to one question: do you believe in what you’re selling? If yes, then removing fear is the most ethical thing you can do. You’re not tricking someone into buying. You’re clearing the obstacles between them and something that will genuinely help them.

If you don’t believe in what you’re selling, no amount of offer architecture will save you. And it shouldn’t.

Why stacking bonuses usually backfires

This is where most offer advice goes sideways. You’ve read the playbook: add bonuses until the perceived value dwarfs the price. Seven bonus PDFs, a private community, a template pack, three video modules, a monthly Q&A — valued at $4,997, yours today for just $297.

There’s a problem with this approach, and it circles back to fear. When you pile on bonuses, you don’t reduce risk. You increase complexity. The prospect now has to evaluate seven additional things. Their brain, which was already looking for reasons to hesitate, now has more surface area to find them.

Worse — excessive bonuses signal desperation. If the core offer were strong enough, why does it need seven crutches? The prospect doesn’t think this consciously, but they feel it. Something about the offer feels… try-hard.

A better approach: one bonus that directly addresses the most common failure mode. If you sell a fitness programme, the bonus isn’t a meal plan and a meditation guide and a sleep tracker. It’s a “stuck?” hotline — because the fear isn’t about starting, it’s about stalling out at week three. One targeted bonus that speaks to a specific fear outperforms a pile of generic value every time.

Putting this into practice

Next time you sit down to build an offer, don’t start with the price. Don’t start with the bonuses. Start with this question: what is my prospect afraid of right now?

Write down the three fears — wasted money, wasted time, looking foolish. Then ask: which one is loudest for my specific buyer? A first-time purchaser in your category probably fears wasted money. Someone who’s been burned by your competitors fears wasted time. A senior executive spending company budget fears looking foolish in front of their board.

Map one offer element to each active fear. Nothing more. Resist the urge to add anything that doesn’t directly answer a specific concern. Simplicity isn’t the enemy of a strong offer — it’s the evidence of one.

Then test one element at a time. The same offer framed as “money-back guarantee” versus “full refund plus I’ll buy you a competitor’s product” can produce wildly different results. In split tests, simply changing how you articulate a guarantee — without changing the actual policy — can shift response rates by 40% or more.

Your prospect can afford what you’re selling. They’re just waiting for someone to make it safe enough to say yes.

Your Offer Isn’t Weak. It’s Aimed at the Wrong Fear.

Most businesses stack bonuses and slash prices to close the gap. But if your prospect’s real hesitation is wasted time or looking foolish, none of that lands. We’ll map your current offer against the three fear layers — and show you which one is actually killing the sale.

The fix is usually one element, not ten. Takes 15 minutes. You don’t need a bigger offer. You need one that answers the question your prospect is too afraid to ask out loud.