Ben Settle tested it across five different markets — golf, prostate health, weight loss, self-defense, email marketing. Every time, he found the same thing: the more straight teaching he put into his emails, the fewer sales he made.

Not slightly fewer. Measurably, painfully fewer.

The emails that sold? They barely taught anything. One of his highest-converting emails was about a copyright attorney’s cease-and-desist letter he’d posted on his website as a joke. Zero educational content. Two newsletter subscriptions sold before lunch — at $97 a month each.

If you read Your Marketing Isn’t Wrong. It’s Boring, you already know the diagnosis: most content is broccoli. Nutritious, accurate, technically correct — and completely ignored. Alan Alda explained why 60 Minutes became one of the highest-rated shows in television history with six words: “a hotdog that nourishes like broccoli.”

That post was the diagnosis. This one is the recipe.

Because “be more entertaining” is useless advice. It’s like telling someone who can’t cook to “just make it taste good.” You need ingredients. Specific ones. And the good news is that none of them require you to be funny, charismatic, or extroverted. They’re structural moves, not personality traits.

Here are five.

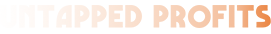

Ingredient 1: The Peter Parker Principle (personality over product)

Stan Lee wrote the first 100 issues of Spider-Man. And what he admitted years later says everything: he didn’t care much about Spider-Man.

He cared about Peter Parker.

The broke teenager who couldn’t pay rent. The kid who fumbled every conversation with Mary Jane. The nephew who worried constantly about Aunt May’s health. Stan Lee’s obsession wasn’t “how can I make the next fight scene cooler?” It was “how can I give this poor kid more problems?”

You’ve felt this pull yourself. Think about the last show you binged. You didn’t stay up until 2 AM because the plot was technically well-constructed. You stayed because you needed to know what happened to a specific person — whether they’d get the job, survive the betrayal, make it home.

Spider-Man is a multi-billion-dollar franchise. But strip away Peter Parker’s personality — the anxiety, the bad luck, the self-deprecating humour — and it’s just another guy in a suit punching things. Spider-Man 2 (2004) is still considered one of the best comic book films ever made, precisely because it’s barely a Spider-Man movie. It’s a Peter Parker movie. The audience came for the superpowers. They stayed for the person.

Your content works the same way. Your product features are Spider-Man — technically impressive, but interchangeable with a dozen competitors. Your personality is Peter Parker. The frustrations you share. The mistakes you admit. The opinions that make some people love you and others unsubscribe.

Try this: In your next piece of content, before you mention your product or teach a single thing, share something real. What’s pissing you off about your industry this week? What mistake did you make recently? What do you believe that most of your competitors would disagree with? That’s your Peter Parker. Lead with that, not the cape.

Ingredient 2: The Everyday Analogy (make the mundane carry your message)

Settle once wrote an email with the subject line “Phantom Pooping Prospects.”

Yes. That’s what it said.

The email told a story about his dog in Oregon, where it rains constantly. He’d take her outside, she’d sniff around endlessly, squat like she was about to go — and then nothing. She’d stand back up and resume sniffing while he stood there getting soaked.

Then the pivot: “This is exactly what selling is like. You have prospects who sniff around, act like they’re going to buy, and then… nothing.” His solution: only sell to people when they’re 90% ready, just like you should only take the dog out when she genuinely needs to go.

That email sold a lot of copies of his book on selling. Not despite the dog poop analogy. Because of it.

Here’s why this works. Your brain processes abstract business advice (“qualify your leads better”) and files it under “yeah, I know.” But a wet man standing in the rain watching a dog fake-poop? Your brain sees that. It builds the scene involuntarily. You smell the rain. You feel the frustration. And when the lesson arrives, it’s attached to a vivid mental image that won’t leave.

You already have material like this. Your drive to work this morning. The argument you had with a contractor. The weird thing that happened at the grocery store. The trick isn’t being creative — it’s training yourself to ask one question about everyday moments: “What is this an analogy for in my business?”

Try this: Before your next piece of content, think about the most mundane or annoying thing that happened to you this week. Now ask: what does this remind me of in my customers’ experience? Write the everyday story first. Tie the lesson in second.

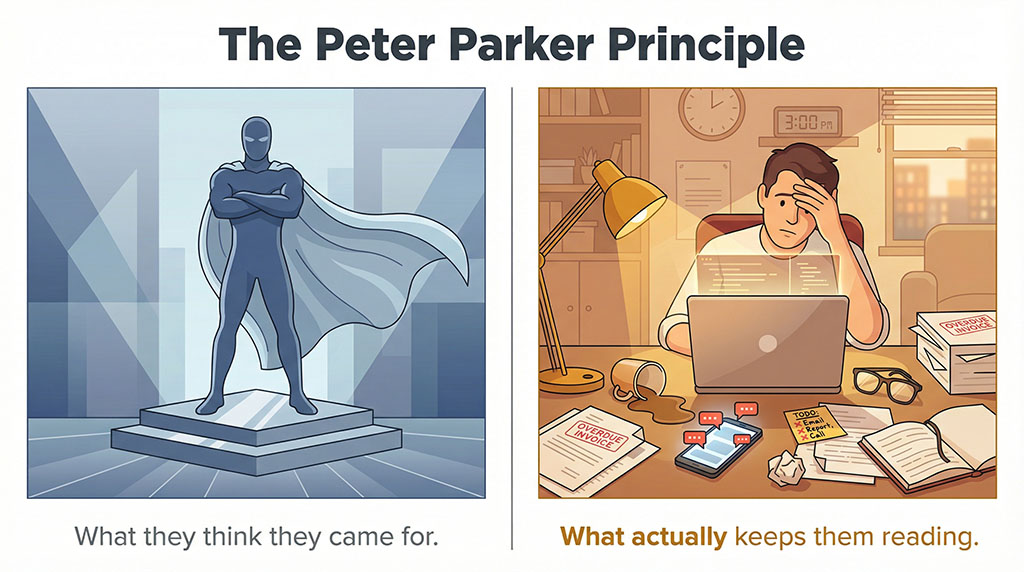

Ingredient 3: The Jester's Privilege (say what you couldn't say with a straight face)

George Bernard Shaw nailed it: “If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh, otherwise they’ll kill you.”

Medieval kings kept royal jesters for a reason most people miss. The jester wasn’t just entertainment — he was often treated as an advisor. He could say things to the king that would get anyone else beheaded, because the comedic framing made dangerous truths feel safe to hear. The laughter was a buffer between the message and the executioner’s axe.

You’ve seen this in modern form. Comedians routinely say things about politics, culture, and human nature that would end a politician’s career. But wrapped in timing and wit, those same truths get standing ovations instead of outrage. The message doesn’t change. The delivery vehicle does.

This is the part of infotainment most people misunderstand. They hear “entertainment” and think the goal is to be funny. It’s not. The goal is to use entertainment as a delivery vehicle — a way to get ideas past the audience’s defences. Dan Kennedy put it simply: people buy more, and buy more readily, when they’re in good humour. Not laughing-out-loud good humour. Just… smiling. Matt Furey’s advice was even more accessible: “At the very least, go for the smile.”

That’s a much lower bar than most people think. You don’t need to write comedy. You need to write something that makes one person, reading alone at their desk at 2pm on a Tuesday, crack a small smile. A wry observation. A slightly exaggerated description of a common frustration. A self-deprecating aside about your own screwup.

Try this: Find the one thing in your industry that everyone thinks but nobody says out loud. Now say it — but with a wink. Not a rant. Not a manifesto. Just the truth, delivered with enough personality that it makes someone’s mouth twitch before they nod.

"But I'm not the entertaining type"

Let’s stop here, because I know what you’re thinking.

This works for people with personality. I sell B2B logistics software. Or I’m an accountant. Or I run a plumbing company. My customers don’t want Peter Parker — they want a spec sheet and a quote.

That voice sounds reasonable. It’s also the reason your last 30 LinkedIn posts got eleven likes — eight of which were from your own employees.

Consider this: if you think your industry is too serious for infotainment, you’re in excellent company. The United States Centers for Disease Control — an actual government health agency — once ran a zombie apocalypse preparedness campaign. Not a metaphor. An actual “what to do when the zombies come” guide, with comic-book-style graphics and tongue-in-cheek survival tips.

The real information was identical to their standard natural disaster preparedness checklist. Same advice. Same practical steps. But the zombie version generated so much traffic it crashed the CDC’s servers. The broccoli version had been sitting on their website for years, dutifully ignored.

And Ben Settle built his infotainment approach selling prostate supplements. Not exactly a glamorous topic. He wrote subject lines like “The Prostate Supplement That Gave Me Wet Dreams” and turned a niche most marketers would treat with clinical seriousness into a personality-driven business generating hundreds of thousands in sales.

The obstacle isn’t your industry. The obstacle is the belief that professionalism means being boring. Those are not the same thing. 60 Minutes covered war, corruption, and political scandal — some of the most serious journalism on television — and it was also one of the most entertaining shows in TV history. Those two things weren’t in tension. They were the same strategy.

You don’t need to be a comedian. You need to be a human who occasionally lets that humanity show up in your content.

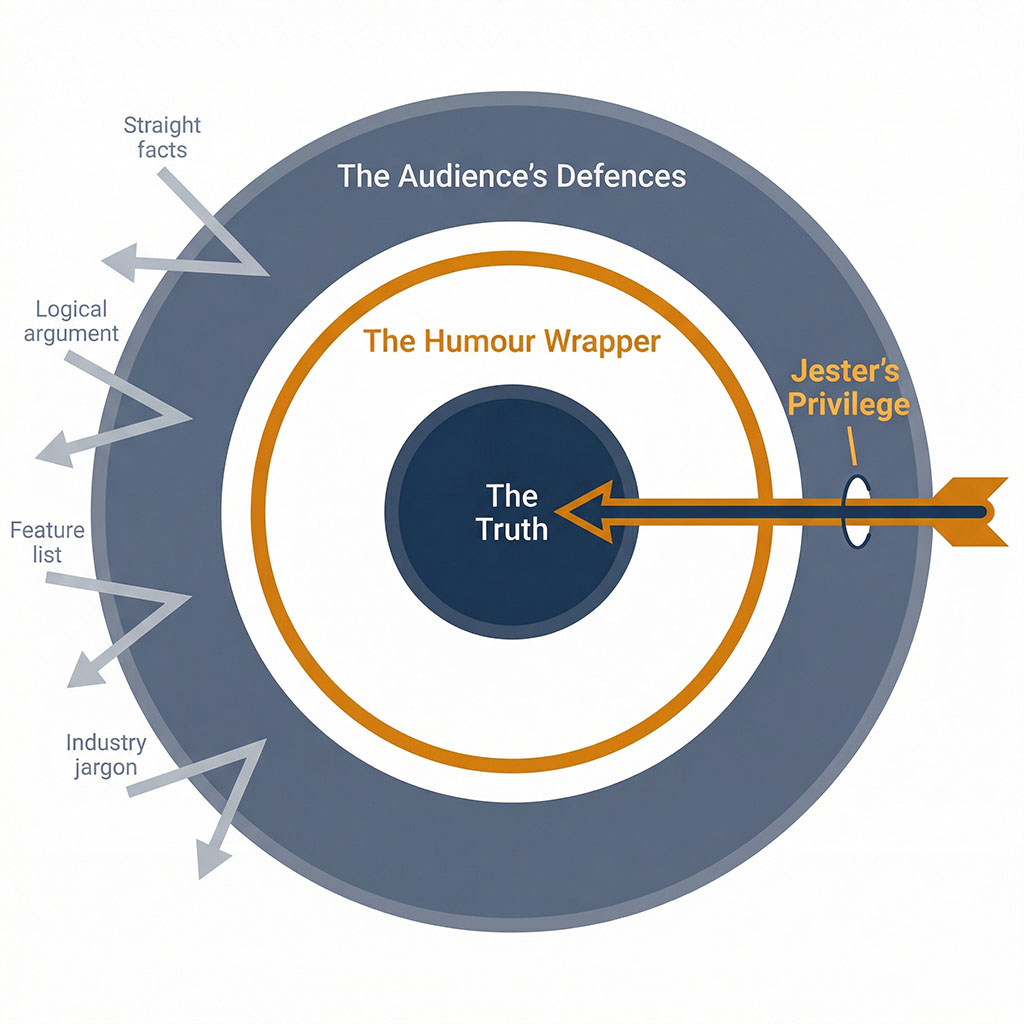

Ingredient 4: Unpredictability (the Red Kryptonite effect)

There’s an old TV show called Smallville — a decade-long series about young Clark Kent before he becomes Superman. Most episodes followed a predictable pattern: Clark faces problem, Clark does the right thing, Clark saves the day. Fine. Watchable. Forgettable.

Then they’d do a Red Kryptonite episode.

Red Kryptonite stripped away Clark’s inhibitions. The mild-mannered farmboy became reckless, selfish, dangerous. He’d hurt people without caring. He’d lie. He’d break things. And those episodes consistently pulled the highest ratings. Not because the audience wanted a villain — but because they couldn’t predict what would happen next.

Predictability is the quiet killer of attention. Your audience builds a mental model of your content: “Oh, it’s another tip post.” “Oh, it’s another product update.” “Oh, it’s another case study with the same three-act structure.” Once they can predict the shape of the thing, they stop actually reading it. They skim. They scroll. They leave.

Comedian Dante Nero calls the principle “consistently inconsistent.” Keep the rhythm unpredictable. If you sent a case study last week, send an opinion piece this week. If your emails are always 500 words, make the next one three sentences. If you always teach, occasionally just rant. If you always agree with industry consensus, pick a fight with it.

The warning: you can become predictably unpredictable. If every piece is a hot take, hot takes become boring. If every email starts with a weird story, weird stories become expected. The goal isn’t chaos. It’s variation. Enough pattern-breaking that your audience opens your next piece thinking “I wonder what this one is” instead of “I know what this one is.”

Try this: Look at your last ten pieces of content. What patterns have you fallen into? Same length? Same structure? Same tone? Pick one pattern and deliberately break it in your next piece. If you always teach, tell a story instead. If you’re always positive, share something that frustrated you. If you always write long, write something you can read in 30 seconds.

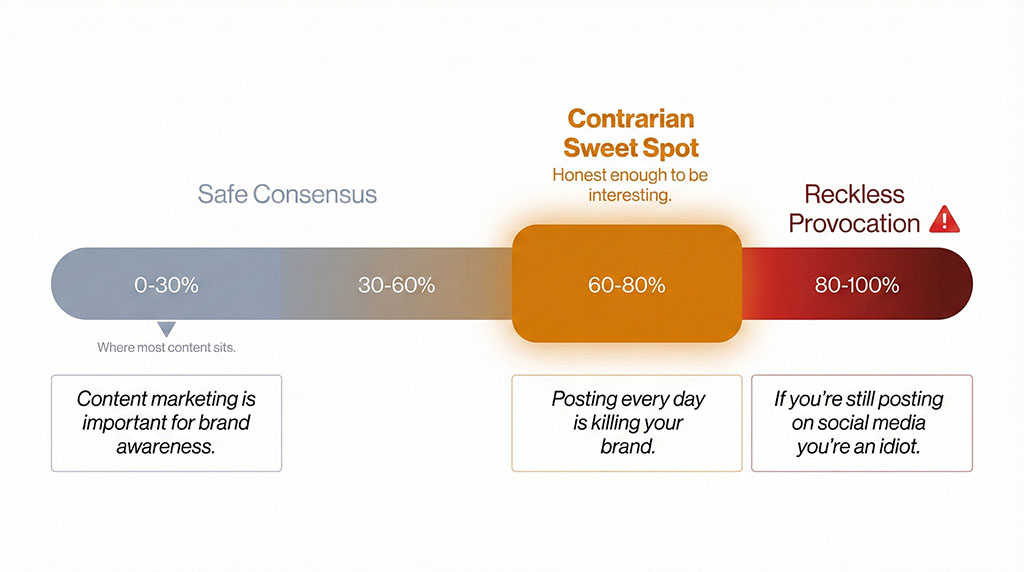

Ingredient 5: Contrarian Positioning (thumb your nose at the establishment)

There’s a health writer named William Campbell Douglass who built an enormous audience by disagreeing with virtually everything mainstream medicine says. Beer is good for you. Eggs won’t kill you. Sunscreen might be doing more harm than good. One of his subject lines — from a medical doctor, mind you — was something like “I start my day with a six-pack and a cigarette.”

Was he being literal? Probably not. Did his audience know that? They weren’t sure. And that uncertainty is what made them open every single email.

You don’t have to be an iconoclast to use this. You just need one opinion that goes against whatever the default advice is in your space. Every industry has a piece of “common wisdom” that most insiders privately think is nonsense. The standard sales funnel. The “post every day” content calendar. The “customer is always right” policy. The belief that more features means more value.

Find the thing everyone nods along to but nobody actually believes, and say what they’re all thinking.

The reason this works isn’t shock value — it’s trust. When someone tells you what you already suspected but nobody else would say, you immediately trust them more. You think: this person isn’t performing. They’re telling me what they actually believe. And in a world where most content sounds like it was written by a committee, one honest contrarian opinion stands out like a flare.

Try this: Complete this sentence: “Everyone in my industry says you should __________, but I think that’s wrong because __________.” If what you wrote makes you slightly nervous to publish — that’s probably the right amount of contrarian. Not reckless. Just honest enough to be interesting.

The cart is right there

Five ingredients. Personality. Everyday analogies. The jester’s delivery vehicle. Unpredictability. Contrarian honesty.

None of them require you to be funny. None of them require a bigger budget, a production team, or a personality transplant. They’re structural choices — decisions about how to deliver information you’re already creating.

The ESPN host who refused to talk about sports on his sports show? He got fired for it. Then he started his own show, did the exact same thing — led with personality, stories, and human connection instead of stats and analysis — and beat ESPN’s ratings in the same time slot.

He wasn’t more knowledgeable than the analysts who replaced him. He was more interesting. And interesting is what gets consumed.

Your content already has the nutrition. The research is there. The expertise is real. The information checks out.

Now picture yourself standing at a hotdog cart. You’ve got all the same ingredients as the broccoli — the substance, the value, the facts. The only question is whether you’ll serve it in a way that makes someone walk over and say “I’ll have one of those.”

The grill is hot. You’ve got five toppings.

Start cooking.

See How Your Content Scores on the Hotdog Test

We’ll take your last 90 days of content and grade each piece against the five infotainment ingredients — personality, analogy, humour, unpredictability, and contrarian positioning. You’ll see exactly which ones you’re missing and where the easiest wins are.

Most clients discover they’re already sitting on stories and opinions worth sharing — they’ve just been burying them under feature lists. Takes 30 minutes.

You don’t need to become an entertainer. You need to stop hiding the interesting parts.