The invoice read $131. For that, the client received a 2,000-word blog post—researched, outlined, written, and edited. Eighteen months earlier, that same deliverable cost $611. Same quality tier. Same turnaround. Same client.

The difference wasn’t inflation running backward. It was the quiet death of a 30-year economic moat.

For three decades, marketing careers were built on a simple truth: execution was hard. Writing code required engineers. Video required videographers. Data required analysts. These technical barriers acted as castle walls—protecting specialists, justifying salaries, creating the illusion that knowing which buttons to click was the same as understanding why. If you could do the thing? You had leverage.

That leverage is evaporating. Not slowly, the way industries usually shift. Fast, the way water drains when someone pulls the plug.

The Inversion Nobody Saw Coming

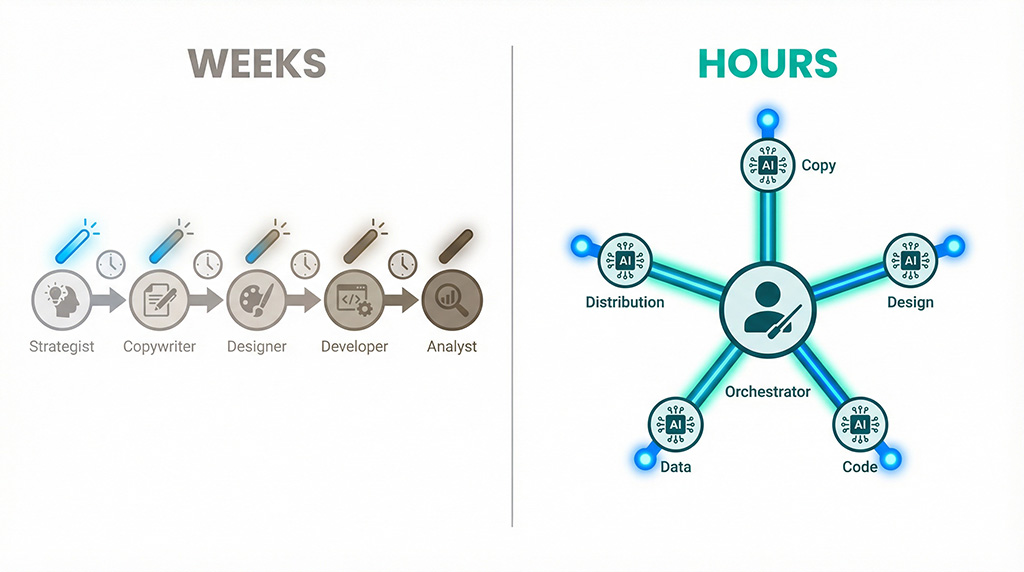

The math is stark. AI-generated content now costs 4.7 times less than human-generated content. A single generalist with the right tools produces what used to require a five-person team. And here’s the number that should make every specialist pause: as of late 2024, more articles are being created by AI than by humans.

You can feel it in the silence of a Slack channel that used to ping with revision requests. In the speed at which “Can you mock this up?” becomes “Here are three options—which direction?” In the particular anxiety of a specialist watching their inbox thin.

But the real shift isn’t about volume or cost. It’s about where value lives in the marketing supply chain.

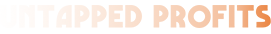

Picture the old model. A strategist defines the campaign. Briefs a copywriter. The copywriter drafts, hands files to a designer, who finishes layouts, passes assets to a developer, who builds the landing page, then waits—always waiting—for an analyst to implement tracking. Five handoffs. Five chances for the original intent to degrade. A game of telephone where the message started as “bold and irreverent” and arrived as “blue button, sans-serif font.”

This relay race created jobs. Lots of them. But it also created the appearance of complexity that justified specialist billing rates. The dirty secret of agency work was always that much of the “expertise” was simply knowing which buttons to click in software that changed its interface every six months.

Now imagine the new model: One person defines the strategy, uses AI to generate copy variations, uses AI to produce design concepts, uses no-code tools to deploy, and uses AI to analyze results. Not perfectly—we’ll get to that. But fast. And cheap. And without the accumulated misinterpretation of four handoffs.

The specialist’s moat wasn’t knowledge. It was execution difficulty. And execution difficulty just went to zero.

The Rise of the Orchestrator

If the specialist is threatened, the generalist is liberated. But not the old “jack of all trades, master of none” generalist—someone new.

Emily Kramer, who built marketing at Asana and Carta, calls them “Pi-shaped marketers.” The metaphor matters: these aren’t shallow generalists who know a little about everything. They have deep expertise in two distinct areas—say, growth marketing and product marketing—plus broad fluency across the rest. They span what Kramer calls the “Fuel and Engine” divide: Fuel is content, brand, messaging (what you say), and Engine is distribution, operations, growth (how it spreads). Traditional specialists sit on one side. Pi-shaped marketers bridge both.

But AI pushes this further. We’re now seeing what some call “O-shaped” professionals—people who use AI to artificially create depth in areas where they lack formal training. A strategist who never learned to code can now “spike” in development by knowing what to ask the machine to build. They don’t need to master Python; they need to know what Python should do.

This is the AI Generalist. Not a polymath—a polymath by proxy. Their skill isn’t execution; it’s orchestration. They’re the conductor who can’t play every instrument but knows exactly how each section should sound—and catches the wrong note before the audience does.

The data backs the model. Companies using AI for marketing execution report revenue increases of 3-15% and achieve speeds up to 50% faster. But the more telling proof point is the emergence of what Silicon Valley has started calling “one-person unicorns”—businesses generating millions with a headcount of one.

Brett Williams built DesignJoy into a multi-million-dollar design subscription service with zero employees. No project managers. No meetings. He productized ruthlessly and eliminated every administrative layer. Before generative AI, this required top-1% talent. Post-AI, it’s becoming a replicable playbook. Williams was the prototype; the model now scales to anyone willing to architect their workflow around AI agents instead of human assistants.

"But My Expertise Still Matters"

Here’s where you push back. You’ve spent a decade becoming the SEO person, the paid media person, the analytics person. You’ve seen AI output. It’s mediocre at best. It hallucinates. It misses nuance. It produces what the research calls “AI slop”—content that meets the minimum threshold of coherence but fails to achieve resonance.

Your clients still call you when the campaign breaks. Surely that depth has value?

It does. But not the way you think.

The threat isn’t that AI replaces you directly. It’s that a generalist wielding AI now achieves 80% of your output at 20% of your cost. For most business decisions, “80% as good, 5x cheaper” wins. Not for everything. Not for the highest-stakes work. But for the vast middle of the market—the bread and butter of most specialists—the math has flipped.

I’ve watched this play out in real time. A client who used to need a full content team now runs their entire blog operation with one marketing manager and a Claude subscription. They didn’t fire anyone dramatically—they just stopped backfilling when people left. The work kept shipping. Nobody outside the team noticed the difference.

There’s a quality ceiling. AI content hits a wall of diminishing returns. It’s trained on the average of the internet, so it produces average work by definition. It struggles with subtext, sarcasm, high-context humor—anything requiring genuine cultural fluency. Companies that rely 100% on automated content end up with brand erosion, a “sea of sameness” where distinctiveness evaporates.

But here’s the knife’s edge: the generalist who understands this ceiling and knows when to override the machine is more dangerous than the specialist who can only execute their one discipline manually. The generalist ships faster, iterates more, and calls in the specialist only for the 20% that truly requires mastery.

Your expertise still matters. It just doesn’t justify full-time employment anymore. It justifies a contractor rate for the moments when “good enough” would be “brand-destroying.”

The Ladder That Disappeared

The structural implications run deeper than individual careers. The marketing industry is eating its own seed corn.

Entry-level jobs—data entry, basic copywriting, junior research—are the most susceptible to automation. One survey found AI is eliminating entry-level positions at 52% of companies. These weren’t just jobs; they were apprenticeships. The grunt work that taught pattern recognition, developed instincts, built the tacit knowledge that eventually produces senior strategists.

Consider a logistics analogy: A dispatcher learns to “sense” a port clog before it happens by managing thousands of shipments over years. That gut instinct doesn’t come from training manuals; it comes from reps. If AI manages the shipments, the dispatcher never develops the intuition.

Marketing works the same way. There’s a specific kind of learning that only happens at 11 PM, three weeks into a failing campaign, when you finally see the pattern your manager tried to explain in the kickoff meeting. That learning requires failure. It requires reps. And we’re automating the reps.

You learn to sense a bad campaign by running hundreds of bad campaigns. You learn to recognize a winning headline by writing thousands of losing ones. If juniors don’t do the grunt work—if AI handles the production that used to be their training ground—how does the next generation develop strategic judgment?

The org chart is inverting. Traditional pyramids (CMO → VPs → Directors → Managers → Juniors) are becoming hub-and-spoke networks: a small core of senior orchestrators managing AI agents and a flexible periphery of specialist contractors for last-mile work. The middle is getting squeezed out. Mid-level managers whose job was supervising juniors have no juniors to supervise.

Career growth used to mean climbing—managing more people. Now it means expanding—managing more complex workflows. The analyst becomes a strategist. The copywriter becomes a brand architect. Moving sideways into adjacencies replaces moving upward through hierarchy.

But this only works for people who make the transition. For those who defined their value by managing specialists who are no longer hired, the path forward is unclear.

The New Scarcities

When execution becomes a commodity, what remains scarce?

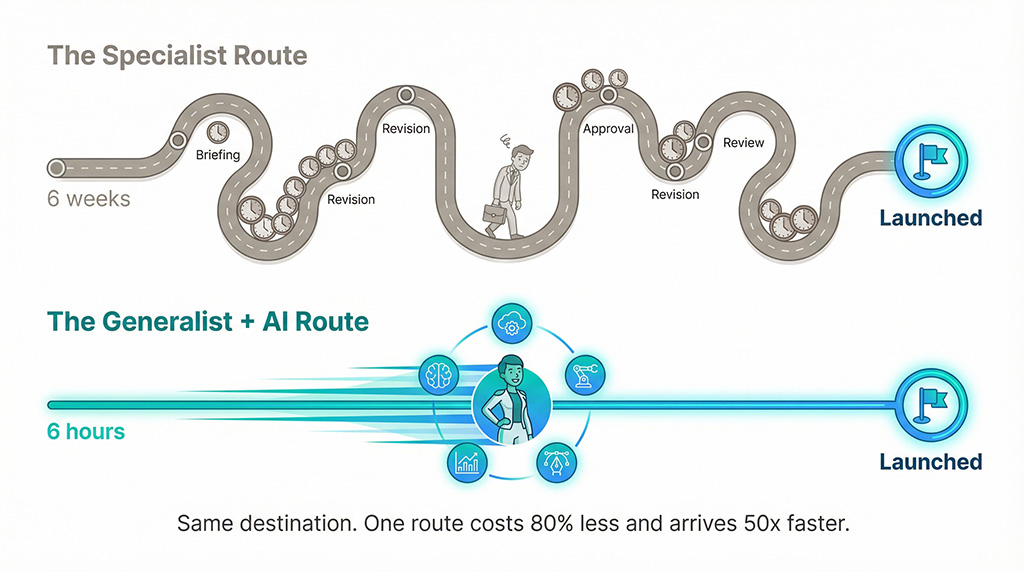

Taste. When AI generates 100 headline variations in seconds, the skill isn’t writing the headline—it’s choosing the right one. This requires intuitive understanding of brand voice, cultural context, audience psychology. The orchestrator’s job is editor-in-chief of a silicon writing staff, curating the output rather than producing it.

Strategy. The research frames it bluntly: “Execution is cheap; decisions are expensive.” The cost of a wrong decision is high even when executing that decision costs nothing. Differentiation strategy—why should a customer choose you when ten competitors look identical?—remains beyond what autonomous agents can solve.

Trust. Here’s the counter-wave: 84% of Gen Z trust brands more when they see actual customers rather than polished content. As AI floods the web with synthetic media, proof of humanity becomes a luxury good. The orchestrator must know when to stop using AI and insert their own face, voice, and story.

This is the “human-in-the-loop” not as quality control but as signal. In a world of infinite AI content, your willingness to show up—imperfectly, recognizably human—becomes differentiation itself.

What the $131 Doesn't Buy

The invoice that opened this piece—$131 for a blog post—represents the new floor. Anyone can hit it. Any competitor with a Claude subscription and a few hours of practice can produce that same deliverable at that same cost.

Which means the $131 post is worthless as differentiation. It’s table stakes. The minimum viable artifact in a market drowning in minimum viable artifacts.

What the $131 doesn’t buy: the judgment to know that this particular post shouldn’t exist at all. The taste to recognize that the AI’s third variation captured the brand voice while the first two felt hollow. The strategic clarity to understand how this post fits into a larger narrative arc that moves the customer from skepticism to trust over six months. The human willingness to attach your name and reputation to the claim—to be accountable when it’s wrong.

The specialist who mastered execution built a career on the $611 version of that post. That career model is over. Not declining. Over.

The new career model belongs to the orchestrator who treats the $131 as raw material—cheap, abundant, instantly available—and adds the irreplaceable layer on top: deciding what to make, recognizing when it’s good, and having the taste to know the difference.

The moat didn’t move. It drained entirely. The only question now is whether you’re standing in the mud or learning to build on higher ground.

Book Your Agency Waste Audit

Find out if your marketing team is built for the $131 era – or still paying $611 prices.

Most teams discover 40-60% of their specialist budget is now automatable. Assessment takes 5 minutes.

The moat already drained. The only question is whether you’re building on higher.