The cable snapped. The crowd screamed.

It was 1854, and a man named Elisha Otis was standing on an open elevator platform, 50 feet above a crowd at the New York Crystal Palace. He’d asked an assistant to sever the only rope holding him in the air. With an axe.

For three horrifying seconds, nothing happened. Then the platform lurched — and dropped exactly four inches. Otis steadied himself, looked down at the crowd, and said two words: “All safe.”

He was selling a safety elevator. The problem? Nobody trusted elevators. They’d been killing people for years. Otis could’ve taken out newspaper ads. He could’ve published testimonials. He could’ve hired a persuasive salesman to knock on doors and explain the engineering behind his patented ratchet mechanism.

Instead, he cut the rope.

That single act — a 90-second stunt in front of a live audience — did more to sell safety elevators than every written argument in the world could have. Within a decade, Otis elevators were in buildings across America. His company still exists today.

And the principle he stumbled onto hasn’t aged a day.

Claims are cheap. Demonstrations are expensive to fake.

Here’s what Otis understood that most marketers still don’t: there’s a fundamental difference between telling someone your product works and making them a witness.

Every ad, every landing page, every sales pitch makes claims. “Our software saves you 10 hours a week.” “Our coaching program transforms your results.” “Our product is better than the competition.”

The prospect’s brain hears all of it the same way: That’s what you would say.

This isn’t cynicism. It’s pattern recognition. Your prospect has been lied to by thousands of ads. They’ve bought products that didn’t deliver. They’ve sat through pitches where the reality was half the promise. Their default setting — correctly — is distrust.

A demonstration short-circuits that distrust because it shifts the burden of proof. You’re not asking them to believe your words. You’re asking them to believe their own eyes.

Drayton Bird, who spent decades running Ogilvy & Mather Direct, put it more bluntly: “An ounce of demonstration beats a ton of bullshit.”

He wasn’t being crude. He was being precise.

Why the best demonstrations feel like a stunt

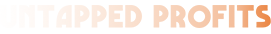

The examples that stick — the ones people share and remember years later — all have something in common. They don’t just show the product working. They show it working under conditions designed to make it fail.

Think about what Otis did. He didn’t demonstrate the elevator going up and down smoothly. He severed the cable. He engineered the worst-case scenario and dared the product to survive it.

That’s the formula: stress test, not showcase.

Blendtec understood this. Tom Dickson didn’t demonstrate his blenders by making a smoothie. He dropped an iPhone into one. Marbles. A rake handle. Golf balls. The “Will It Blend?” series worked because the question wasn’t can this blender blend fruit — nobody doubts that. The question was what can’t it blend? Each video was a public stress test, and when the answer kept coming back “nothing,” the proof was undeniable.

GoPro took the same approach from a different angle. They never ran product demos. They handed cameras to surfers, skydivers, and mountain bikers — people whose environments destroy cameras — and published the footage. The footage was the demonstration. If a GoPro survives a 50-foot wave and the video looks that good, you don’t need spec sheets.

Purple Mattress made their core claim physical. They dropped a raw egg from four feet onto the mattress. It didn’t break. Then they showed what happened on a competitor’s mattress. The egg shattered. Years of mattress advertising had told people things like “pressure relief” and “responsive support.” Purple showed an egg surviving a fall. One image replaced a thousand adjectives.

OxiClean’s entire infomercial empire was built on a single repeated demonstration: stained fabric goes in dirty, comes out clean. Billy Mays didn’t explain the chemistry. He didn’t talk about oxygen-based surfactants. He poured wine on a white shirt, dunked it in OxiClean, and held it up. Over and over. The repetition wasn’t lazy — it was strategic. Each stain was a new stress test, and each clean shirt was another piece of evidence stacking up.

Notice the pattern. None of these demonstrations said “trust us.” They all said “watch this.”

"But I don't sell blenders."

Right. And this is where most people check out.

They see Blendtec and GoPro and think that’s cute for physical products, but I sell consulting. I sell software. I sell something you can’t drop an iPhone into. The demonstration principle sounds great in theory, but it feels like it belongs to the world of infomercials and YouTube stunts — not to serious B2B or service businesses.

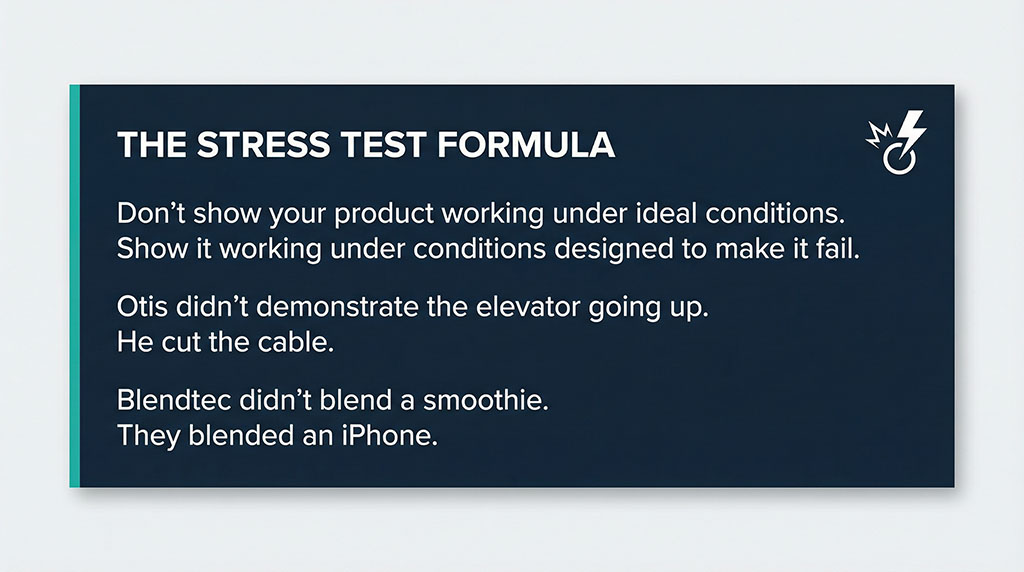

Here’s the thing: every one of those infomercial-style demonstrations is just a compressed version of something you can do in any business. The principle isn’t “destroy something on camera.” The principle is collapse the gap between your claim and their proof.

And that gap exists in every industry.

A consultant who tells you they can find inefficiencies in your operation is making a claim. A consultant who shows up, spends 30 minutes looking at your processes, and identifies three specific problems on the spot — that’s a demonstration. The prospect didn’t have to trust the claim. They just experienced the proof.

A SaaS company that tells you their tool saves 10 hours a week is making a claim. A SaaS company that gives you a free audit of your current workflow and shows you exactly where those 10 hours are hiding — that’s a demonstration. The free trial isn’t the demonstration. The personalised diagnosis is.

A financial adviser who tells you they can improve your portfolio is making a claim. One who shows you a side-by-side of how your current allocation would have performed versus their model over the last five years using your actual numbers — that’s a demonstration.

The format changes. The principle doesn’t. Find the gap between what you claim and what they believe, then close it by making them a witness.

The seven intensifiers (and how they actually work)

Once you’ve got a core demonstration, there are specific ways to amplify its impact. These aren’t abstract theories — you can see each one operating in the examples above.

Show it live. The reason Otis stood on the platform instead of sending an assistant is the same reason cooking shows crack eggs on camera. Showing it in real time removes the suspicion of editing, staging, or trickery. If you can demonstrate your product working live — in a webinar, on a sales call, on a trade show floor — the credibility multiplies.

Make the viewer the protagonist. The best demonstrations put the prospect inside the experience. “Imagine this is your stained shirt.” “Imagine this is your current ad spend.” The moment you shift from look what our product does to look what happens to your specific problem, you’ve moved from proof to desire.

Extend the timeline. A demonstration shows what happens now. A great demonstration shows what happens in six months. Purple doesn’t just show the egg surviving — they show the mattress maintaining its form after thousands of compressions. Before-and-after is powerful. Before-during-and-after-six-months is more powerful.

Bring in the referee. Expert endorsement works, but not the way most brands use it. A celebrity holding your product is advertising. An engineer explaining why the mechanism works is a demonstration. The difference is specificity — the expert has to explain why, not just say yes.

Run the side-by-side. Put your product next to the alternative and test them under identical conditions. This is what Purple did with the egg test. It’s what every car wax infomercial does when they spray water on two hoods. Side-by-side isn’t just comparison — it’s a controlled experiment your prospect can watch in real time.

Make ease visible. If your product is simpler to use, show the complexity of the alternative first. The Transforma Ladder infomercial doesn’t start by showing the Transforma. It starts by showing a guy wrestling with three different conventional ladders, nearly falling off a roof. By the time the Transforma appears, the contrast does all the selling.

Use an unexpected metaphor. Otis used death as his metaphor. He didn’t demonstrate safety — he demonstrated the absence of danger. The iPhone in the blender works because it’s absurd. The raw egg on the mattress works because eggs are fragile. When your demonstration borrows drama from an unexpected source, it becomes a story people retell.

You won’t use all seven in a single demonstration. Pick the two or three that match your product and your prospect’s objection. A service business might lean heavily on “make the viewer the protagonist” and “run the side-by-side.” A physical product might lead with “show it live” and “use an unexpected metaphor.”

The point isn’t to check boxes. It’s to ask: what’s the single most convincing thing I could show someone, and how do I make it impossible to dismiss?

The demonstration you're already not doing

Most businesses have a demonstration hiding inside their process. They just haven’t extracted it.

Your case studies are demonstrations waiting to be visualised. Your sales calls contain moments where the prospect’s eyes go wide — those moments are demonstrations waiting to be replicated. Your customer support logs are full of problems your product solves in minutes that used to take days — those are demonstrations waiting to be recorded.

The mistake is thinking a demonstration needs to be a produced video or a dramatic stunt. Sometimes it’s a screenshot. Sometimes it’s a live walkthrough on a Zoom call. Sometimes it’s a free tool that does 10% of what the full product does — just enough for the prospect to experience the result themselves.

The format matters less than the function: did the prospect witness the proof, or did they just read about it?

Elisha Otis died in 1861. His sons took over the company and kept doing exactly what he’d done — installing elevators in the most visible buildings they could find, inviting the public to ride them, making the safety visible.

Today, 2 billion people ride an Otis elevator every day. Not because the engineering was explained well. Because 170 years ago, a man stood on a platform, watched the rope get cut, and let the product speak for itself.

Your product is the safety elevator. The only question is whether you’re asking people to trust the cable — or cutting it in front of them.

See the Proof Before You Pay for It

We don’t pitch. We demonstrate. Book a free Agency Waste Audit and we’ll show you exactly where your current marketing spend is leaking — before you spend a cent with us.

Most clients find 2–3 channels quietly bleeding budget that nobody spotted because nobody looked at the full picture. Takes 30 minutes.

We could tell you we’re different. But Otis didn’t explain the engineering. He cut the rope.