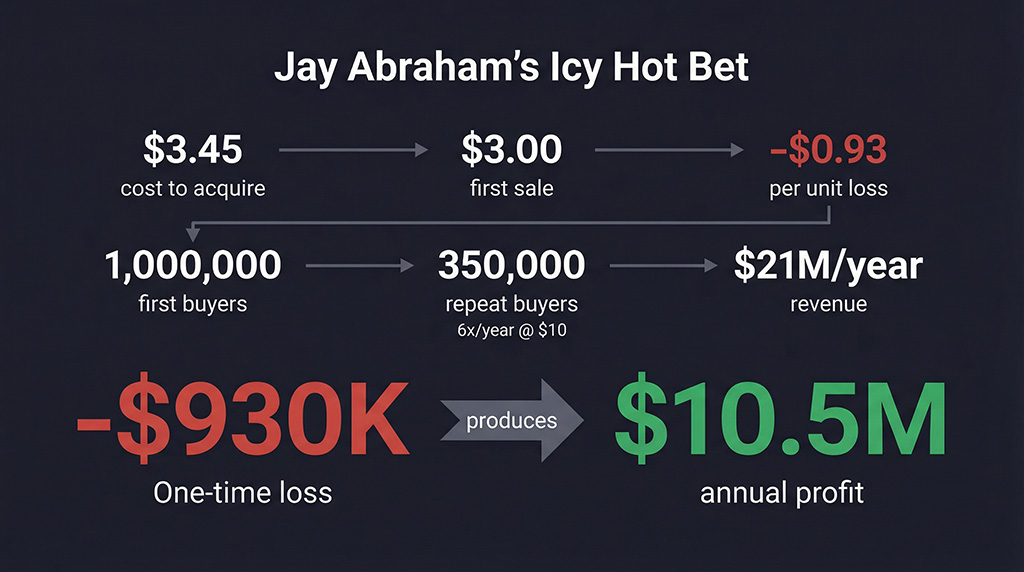

Jay Abraham spent $3.45 to sell a $3 jar of arthritis cream.

Read that again. He paid more in advertising than the product sold for. Every single unit shipped at a loss. His accountant probably needed a drink. His competitors probably thought he’d lost his mind.

He lost 93 cents on every first order. Nearly one million people tried the product. Three hundred and fifty thousand of them came back — at least six times a year — spending an average of $10 per order. That one-time loss of roughly $930,000 generated $21 million a year in revenue, with over half of it as pure profit.

A $930,000 loss produced $10.5 million in annual profit.

Jay wasn’t reckless. He was the most calculated person in the room. Because he knew one number that his competitors didn’t: the lifetime value of his customer. And from that number, he derived the single metric that controls how fast any business can grow.

It’s called the Allowable CPA. And it’s the alternative to the path most businesses are actually on — chasing a perfect ROAS on every campaign, right up to the day they close the doors.

The metric most businesses get backwards

Most advertisers manage to ROAS. They want every campaign to return a profit. It feels safe. It feels responsible. And it slowly strangles their growth.

Here’s the problem: when you engineer every campaign for immediate return, you can only afford to reach the cheapest, most ready-to-buy customers. Your targeting stays narrow. Your bids stay low. Your growth stays incremental. You’re “profitable” in the same way a savings account is profitable — technically positive, functionally standing still.

The metric that changes this is the Allowable CPA.

CPA — Cost Per Acquisition — is a number you calculate after the fact. You spent $1,000, you got 10 customers, your CPA was $100. It’s a rearview mirror.

Your Allowable CPA is the opposite. It’s a decision. It’s the maximum amount you’re willing to invest to acquire a single new customer, set before you launch a campaign — based on what you know that customer will be worth over time.

Two businesses selling the same $100 product with the same 40% margin can set completely different Allowable CPAs. Business A says “I need profit on every first sale” and sets their Allowable CPA at $20. Business B says “I know my customer comes back three more times” and sets theirs at $60.

Business B can now buy customers on channels, in segments, and at volumes that Business A can’t touch. Same product. Same margin. Radically different growth trajectories.

The difference isn’t the product. It’s the math behind the decision.

Two games, one scoreboard

Most businesses treat acquisition and monetisation as one blurred activity. They’re not. They’re two completely separate games with different rules, different tactics, and different objectives.

Acquisition is the campaign you run to buy a new customer today. Its economics are based on what you already know about customer value from historical data.

Monetisation is everything that happens after. The upsell email. The loyalty offer. The seasonal reactivation campaign. Its job is to increase the average value of each customer you’ve already acquired.

Here’s the critical connection: monetisation performance determines your acquisition budget. The better your backend converts, the more you can afford to spend on the frontend. They feed each other — but you measure them separately.

Think of it like a restaurant. Acquisition is getting someone through the door for the first time (maybe with a discount, maybe at a loss). Monetisation is the wine pairing, the dessert menu, the “we have a new tasting menu next month” email that brings them back. The profit isn’t in the first visit. It’s in visits two through twenty.

Your Allowable CPA is set by measuring the monetisation side — then deploying that knowledge on the acquisition side.

How the math actually works (a walk-through)

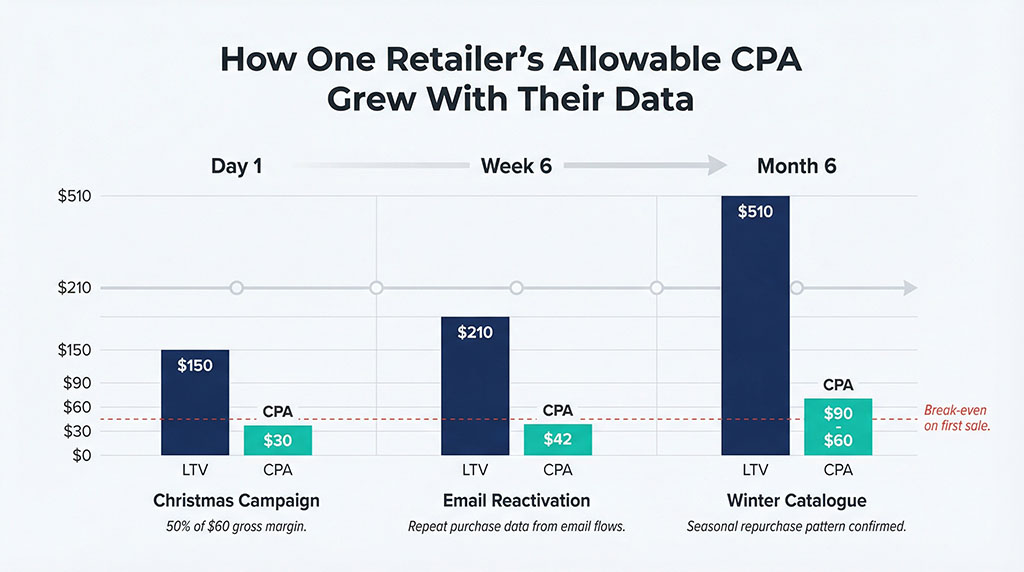

Let’s make this concrete. Say you run a fashion retail brand and you’re about to launch a Christmas campaign.

The starting position: Your average new customer during December buys two items at an average order value of $150. Your margin is 40%, which gives you $60 in gross profit. You decide you’re comfortable investing half that margin — $30 — into acquiring new customers.

Your Allowable CPA: $30.

At $30, you can profitably run ads on Meta, maybe some Google Shopping. You acquire a few hundred customers. You’re making money on every first order. Life is fine.

But then something happens.

Six weeks later, your email flows trigger and the average customer comes back for a $60 purchase. No ad spend required — they’re already on your list. Their total value just jumped from $150 to $210. Your Allowable CPA could now be $42.

Six months later, winter catalogue drops. These same customers are buying coats, boots, heavier items. Average order value on that third purchase: $300. Again, acquired through email — zero incremental ad cost.

Total customer value over six months: $150 + $60 + $300 = $510.

Now do the maths on your original $30 CPA. You’re sitting on a 17x return. But here’s the real question: what if you’d known this from the start?

Instead of a $30 CPA, you could have set $60 — breaking even on the first sale — and doubled the number of customers entering your funnel. Or gone to $90 and accepted a short-term loss, knowing the backend would recover it within weeks.

Every dollar added to your Allowable CPA opens up new channels, new audience segments, new volume. At $30, you’re fishing in a pond. At $90, you’re fishing in the ocean.

"That's great, but I can't afford to lose money on every sale"

Fair. Most business owners hear “go negative on customer acquisition” and picture themselves explaining to their partner why the business account is empty. The Jay Abraham story sounds inspiring when you’re reading about it. It sounds terrifying when it’s your cash flow on the line.

And this is exactly why the ROAS-on-every-campaign approach feels so comfortable. You see green numbers. You sleep at night. The problem is you’re sleeping through your own growth window — competitors who understand their LTV are buying your future customers right now, at prices you’ve decided you “can’t afford.”

But the objection still stands: you can’t go negative if you don’t have the cash to float it. So don’t. That’s a false binary.

The fashion retailer didn’t start at $90. They started at $30 — profitable on day one. They gathered six weeks of data. Raised to $42. Gathered six more months. Raised to $60. Each step was backed by measured customer behaviour, not speculation.

You need exactly two things to start raising your Allowable CPA responsibly:

First, 30 days of repeat purchase data. Not six months. Not a year. Just enough to see whether your first-time buyers are coming back at all, and what they’re spending when they do. If even 15% of your December buyers came back in January, that repeat revenue changes your CPA math.

Second, a simple cohort view. Track customers by acquisition month. How much did the January cohort spend by March? By June? You’re not building a complex attribution model. You’re answering one question: what is a customer worth after 30, 60, and 90 days?

Most businesses already have this data sitting in their Shopify dashboard or CRM. They’ve just never looked at it through the lens of acquisition budgeting.

You don’t need Jay Abraham’s war chest. You need a spreadsheet and 30 days of patience.

Which level are you playing at?

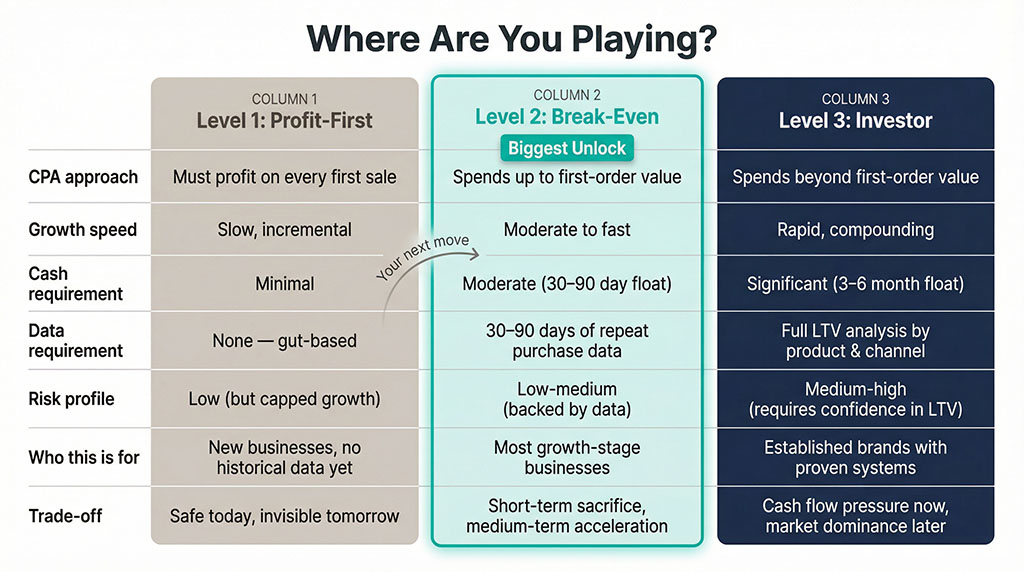

There are three levels of acquisition aggression. Be honest about where you sit right now — and where the math says you could sit.

Level 1: Profit on every sale. You set your CPA to guarantee margin on the first transaction, regardless of whether it’s a customer’s first purchase or their tenth. Your budgets are probably fixed for the year. Growth is slow and incremental. This is where most businesses live — not because the math demands it, but because the math has never been done.

Level 2: Break-even on the first sale. You spend up to what the customer’s first order is worth, covering operating costs but accepting zero profit on the initial transaction. You’re betting that monetisation (email, upsells, repeat purchases) turns that customer profitable within 30–90 days. Growth accelerates because your Allowable CPA just doubled or tripled compared to Level 1.

Level 3: Negative on the first sale. You spend more than the first order is worth, knowing the customer’s lifetime value covers it. This is Jay Abraham territory. A $930,000 loss producing $10.5 million per year. This requires confidence in your LTV data, enough cash to float the gap, and a monetisation engine that reliably converts. But when it works, it doesn’t just scale — it compounds.

The jump from Level 1 to Level 2 is where most of the growth unlock happens. It doesn’t require going negative. It doesn’t require deep pockets. It requires knowing your customer’s 90-day value and being willing to invest again

The flywheel nobody talks about

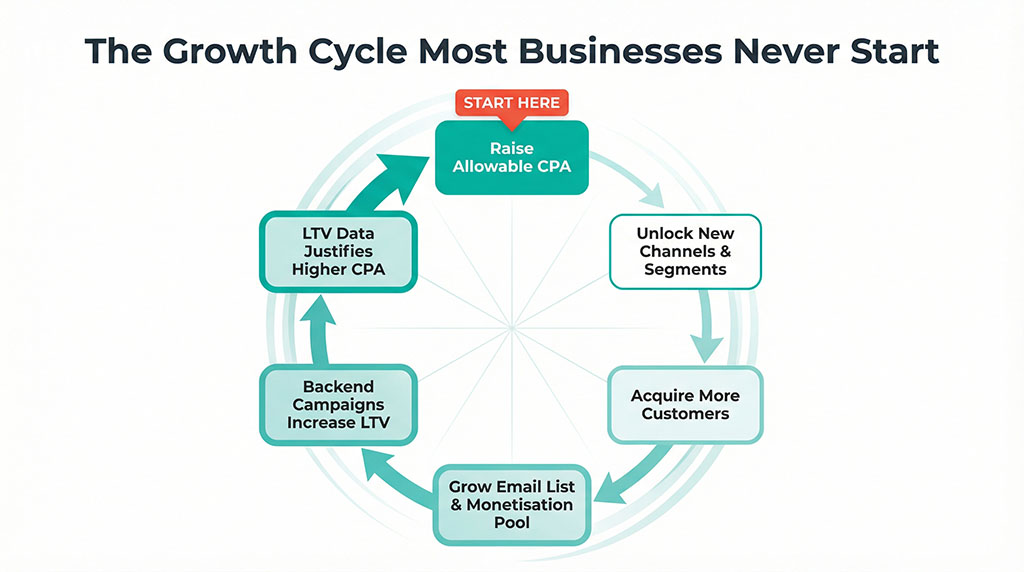

Here’s what changes when you start actively managing your Allowable CPA instead of leaving it on autopilot:

You raise your Allowable CPA from $30 to $60. That opens up audience segments that were previously too expensive — broader targeting on Meta, higher bids on Google, maybe YouTube or direct mail for the first time. You acquire more customers. Your email list grows faster. Your monetisation campaigns have a larger pool to work from — which drives up average LTV — which means you can raise your Allowable CPA again.

It becomes a growth cycle. More customers in, higher value per customer, more money available to acquire the next batch. Each revolution of the wheel makes the next one easier.

This is the exact mechanism that separates brands doing $1M/year from brands doing $20M/year on the same product. It’s not a better ad creative. It’s not a better landing page. It’s a higher Allowable CPA, backed by a monetisation system that justifies it.

And notice: this has nothing to do with conversion rate. You could have a 1% conversion rate and be scaling aggressively, because your Allowable CPA accounts for the backend value. Conversion rate is a vanity metric if you don’t know what a customer is worth after 90 days.

One number, one question

Bonobos — the menswear brand — figured out that customers who bought suits were more likely to come back and make repeat purchases than customers who bought t-shirts. So they led their acquisition campaigns with suits. Not because suits had the highest first-order margin, but because suit buyers had the highest LTV.

That single insight — which product creates the best customers, not just the best first sale — changed their entire acquisition strategy. And it started with one question: what is this customer worth after six months?

If you remember one thing from this piece, make it this: your Allowable CPA is not a number your finance team sets once a year. It’s a living metric that should update every time you learn something new about customer behaviour.

Run the LTV analysis by product. By acquisition channel. By campaign. You’ll find that some campaigns produce customers worth five times more than others — and that knowledge lets you shift budget toward what actually builds the business.

Jay Abraham wasn’t gambling when he lost 93 cents on every jar of Icy Hot. He was making the most informed bet in the room. The only question is whether you know your numbers well enough to make the same call.

Your Allowable CPA is either a growth engine or a growth ceiling. The businesses chasing perfect ROAS on every campaign? They’ll look great on a dashboard right up until someone with better LTV data outbids them on every channel that matters.

Find Out What Your Allowable CPA Should Actually Be

We’ll map your current acquisition costs against your real customer value — and show you the gap between what you’re spending to acquire customers and what you could be spending to grow faster.

Most businesses we audit are running Level 1 CPA targets on products that could support Level 2 or 3 — they just haven’t done the LTV math yet. Takes 15 minutes.

You don’t need a bigger ad budget. You need to know what a customer is actually worth after 90 days.