The dashboard looked fine. That was the problem.

Swimming Pool Kits Direct was running ads to people searching for DIY pool kits. Buyer’s guides. Product comparisons. Price breakdowns. The CPA was acceptable. The ROAS was decent. Every metric said “keep going.”

But “decent” has a ceiling. And we’d hit it.

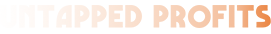

The ads only spoke to people who’d already decided to build a pool themselves. People who typed “pool kit” into Google at 11 PM because they’d already done the research, already watched the YouTube videos, already decided they had the skills. That audience exists. It’s also tiny. And every pool kit supplier in Australia was fighting over the same sliver of search traffic with the same benefit-driven headlines.

The account didn’t need a better hook. It needed a bigger idea.

A "hook" finds better words. A big idea finds new people.

Most advertisers treat “big idea” as a synonym for “clever angle.” A punchier headline. A sharper hook. A benefit framed in a way the market hasn’t quite heard before.

That’s not a big idea. That’s copywriting. Good copywriting, sure—but it’s still a conversation with the same people about the same thing.

David Ogilvy said it takes a big idea to get consumers to buy your product, and that fewer than one in a hundred campaigns contain one. He was right. But here’s the part people miss when they quote him: a big idea doesn’t just grab attention within your existing audience. It creates an audience that didn’t exist before.

Think about the difference:

It’s not a book about “how to outsource.” It’s “The 4-Hour Work Week.” That title didn’t find better words for the same freelancer audience. It pulled in burnt-out corporate workers who’d never searched for outsourcing in their lives.

It’s not about “a new fitness workout.” It’s “P90X Muscle Confusion.” That didn’t speak to gym rats. It spoke to people who’d quit gyms because nothing worked.

It’s not about “a new type of coffee.” It’s “Bulletproof Coffee.” That didn’t target coffee snobs. It pulled in biohackers and productivity obsessives who thought coffee was bad for them.

Each of those ideas expanded the market. They didn’t say the same thing louder. They said something different—to someone new.

The constraint nobody was talking to

Back to the pool account. When I dug into the market, the maths were obvious. The people searching for “DIY pool kit” were a fraction of the people who wanted a backyard pool. Tens of thousands of Australian families were getting quotes from pool companies—$60,000, $70,000—and walking away defeated. Not because they didn’t want the pool. Because they assumed installation required specialised expertise they didn’t have.

That assumption was the lock. And nobody in the pool kit market was picking it.

Every competitor’s ads said the same thing: great price, quality kit, fast delivery. All aimed at the small group who’d already gotten past the expertise fear on their own. The massive segment sitting behind that fear? Invisible to the entire category.

The big idea wasn’t a better headline for pool kits. It was naming the enemy: the “Expertise Illusion.”

Pool companies had built a myth—that installation requires years of specialised knowledge only they possess. But the local excavator already digs pool holes monthly. The local plumber handles systems far more complex than three pool pipes. The “expertise” was a story told by salespeople who charge $30,000 to make three phone calls to the same contractors you drive past every day.

Once you name that enemy, the big idea writes itself.

The Pool Owner's Playbook

We built a campaign around a free guide called “The Pool Owner’s Playbook.” Not a buyer’s guide. Not a product brochure. A playbook—the word matters, because everyone understands a sports playbook. It means: here’s the proven strategy, follow the steps, win the game.

The playbook showed families two paths. Path one: coordinate local trades yourself using the manufacturer’s installation guide, save 50–70%. Path two: work with recommended installers who’ve already rejected the pool industry’s markup games, save 30–40% with zero coordination on your end.

Both paths bypassed the pool company salesman entirely. Both positioned the buyer as the one in control. And both spoke directly to the constraint that kept thousands of families out of the market: “I don’t know enough about pools to do this.”

The campaign didn’t target people searching for pool kits. It targeted families dreaming about pools who’d been told—by an industry with a financial incentive to say so—that they couldn’t do it without paying $60K.

That’s what a big idea does. It doesn’t compete harder for the same 2% of the market. It goes after the 98% nobody else is talking to.

"I don't have time for philosophy. I need hooks that convert."

Fair. I’ve sat in that chair. Tuesday launch date, budget approved, creative needed yesterday. The idea of pausing to think about “big ideas” feels like a luxury you can’t afford.

But here’s what the performance dashboard won’t tell you: your best-performing hook is still fishing in the same pond as every competitor. You’re all fighting over the same intent-based searches, the same remarketing pools, the same lookalike audiences built from the same seed lists. The hooks get sharper. The audience gets smaller. The CPAs creep up. And you call it “market saturation” when really it’s idea saturation.

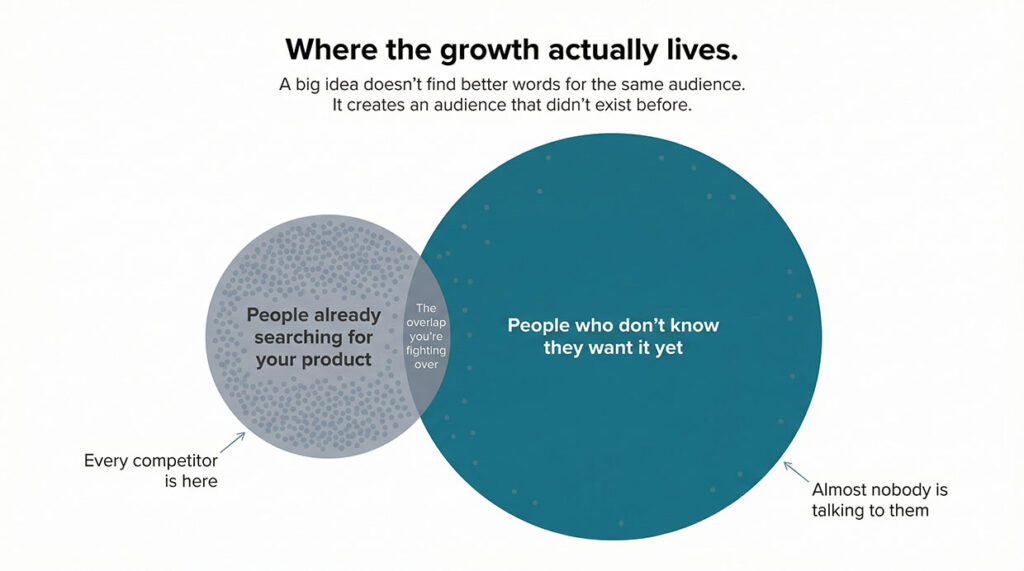

The 60 seconds it takes to stress-test your idea against four criteria costs less than a single wasted ad set.

The four-part test (60 seconds, be honest)

A big idea—one that actually expands your market—passes all four of these. Most campaigns pass one or two and call it done.

Does it hit them emotionally before logically? The Pool Owner’s Playbook didn’t lead with price savings. It led with the feeling of being conned—the frustration of a $60K quote from a salesman who’s never held a shovel. Emotion opens the door. Logic furnishes the room. If your idea leads with features or savings, you’re starting in the wrong place.

Does it feel like a discovery? Your prospect should feel like they’ve stumbled onto something nobody else is talking about. “Cheap pool kits” is information. “The Expertise Illusion” is a discovery. One is a product listing. The other makes someone lean forward and say “wait, what?”

Does it show them a clear path forward? An idea that makes people curious but not confident is just entertainment. Two paths—full DIY or guided coordination—gave every prospect an entry point that matched their comfort level. No one felt left behind.

Does it create urgency without faking it? The best urgency isn’t a countdown timer. It’s the realisation that summer is coming, the kids are getting older, and every year you wait is another year you paid for a pool through inaction. The playbook tied to seasonal timing naturally, not through manufactured scarcity.

If your current campaign idea doesn’t pass all four, you don’t have a big idea. You have a headline.

The car accident test

There’s one more filter, and it’s cruder than the four above.

Your advertising needs to be compelling the way a car accident is compelling. You’re driving past, everyone ahead is slowing down, and you’re muttering about the idiots rubbernecking. Then you reach the wreck—and you slow down too. You become the exact person you were just complaining about.

That’s what “compelling” actually means. Not “interesting.” Not “well-written.” Not “clear value proposition.” It means people cannot look away, even when they know they should keep scrolling.

The Expertise Illusion hit that nerve. Families who’d accepted the $60K quote as reality suddenly couldn’t stop reading about how the entire pricing structure was a manufactured myth. Not because the writing was clever. Because the idea was big enough to break a belief they’d held for years.

Make your big idea so compelling that people can’t scroll past it—even when they’ve told themselves they’re done looking at pool ads for the nig

Back to the dashboard

The Swimming Pool Kits Direct account still runs product ads to DIY searchers. Those campaigns still perform fine. “Fine” is fine for what it is.

But next to them now sits a second set of campaigns. Different targeting. Different message. Different audience entirely. Families who never would have typed “pool kit” into a search bar—because until the Playbook hit their feed, they didn’t know that was an option.

Same product. Same company. Same budget constraints. The only thing that changed was the idea.

Your campaigns have a version of this sitting in front of you right now. There’s an audience adjacent to your current one, held back by a belief, a fear, or an assumption that nobody in your market is addressing. Your competitors are too busy writing better hooks for the same people.

The question isn’t whether you can write a better headline. It’s whether you can find the idea that makes the headline unnecessary—because the concept alone is too big to ignore.

That’s the difference between a hook and a big idea. One gets a click. The other gets a market.

Find the Big Idea Your Competitors Are Missing

We’ll map your current campaigns against the market your ads aren’t reaching — and identify the audience sitting behind constraints nobody’s addressing.

Most clients discover they’re fighting over 10% of their market while 90% goes untouched. Takes 30 minutes.

You don’t need a better hook. You need an idea big enough to make the hook unnecessary.