The ad was gorgeous. Studio-lit product shots. A soaring soundtrack. Copy that hit every benefit on the brief. The client had spent $40,000 producing it and another $25,000 pushing it across Meta and YouTube.

Three weeks in, the results were brutal. A 0.4% click-through rate. Cost per acquisition so high the finance team started CC’ing the CEO on media reports. The ad was technically flawless — and emotionally dead on arrival.

Here’s what went wrong: the ad was performing emotion at people. Swelling music. Dramatic transformation. An actor pretending to have a breakthrough moment. It was a brand having feelings in public and hoping the audience would join in.

They never do.

The neuroscientist who accidentally explained advertising

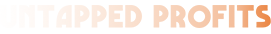

In 1994, Antonio Damasio was studying patients with damage to the ventromedial prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain that processes emotion. These patients could reason perfectly. They scored normally on IQ tests. They could list the pros and cons of any choice laid in front of them.

But they couldn’t decide what to eat for lunch.

Without the ability to feel something about their options, they’d loop endlessly between chicken and turkey, weighing arguments that were perfectly balanced on paper. Damasio’s conclusion reshaped cognitive science: emotion isn’t the enemy of good decisions. It’s the mechanism that makes decisions possible at all.

You’ve experienced this yourself. You’ve stood in a store holding two nearly identical products, read every label, compared every spec — and then just… picked one. Something felt right. You couldn’t articulate why until after the purchase, when you reverse-engineered a logical explanation. “Better ingredients.” “More reviews.” “I liked the packaging.” All true. None of them the actual reason.

That’s not a flaw in human cognition. That’s how human cognition works.

And it’s why the most repeated advice in advertising — “sell with emotion” — is both completely correct and almost completely useless.

Why "sell with emotion" is terrible advice

Everyone knows it. Every marketing blog says it. Every copywriting course teaches it. And yet the vast majority of ads that try to be emotional still fall flat. Why?

Because “sell with emotion” doesn’t tell you which emotion. Or whose emotion. Or when in the buying process that emotion matters most.

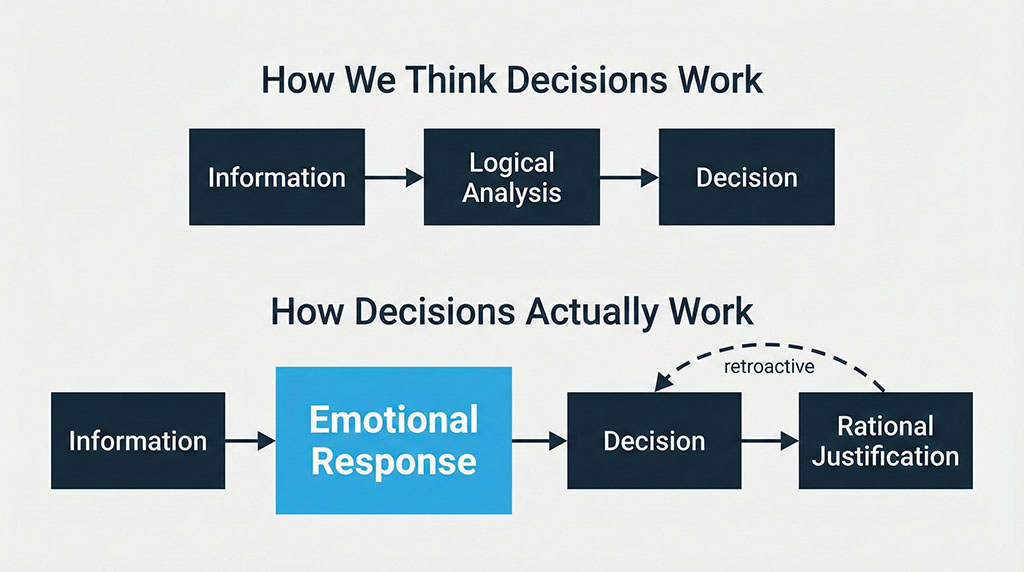

So what happens is predictable. A business owner reads “sell with emotion,” sits down to write an ad, and does one of two things:

They either bolt a feeling onto a feature list — “Our CRM is so easy to use, you’ll feel RELIEVED!” — which reads like a robot trying to pass a Turing test. Or they go full Hollywood: dramatic storytelling, tear-jerking narratives, inspirational montages. Beautiful content. Zero conversions.

Both approaches make the same mistake. They start with the product and try to generate an emotion from scratch.

The best ads don’t generate emotions. They connect to emotions that are already there.

The emotion that exists before your ad does

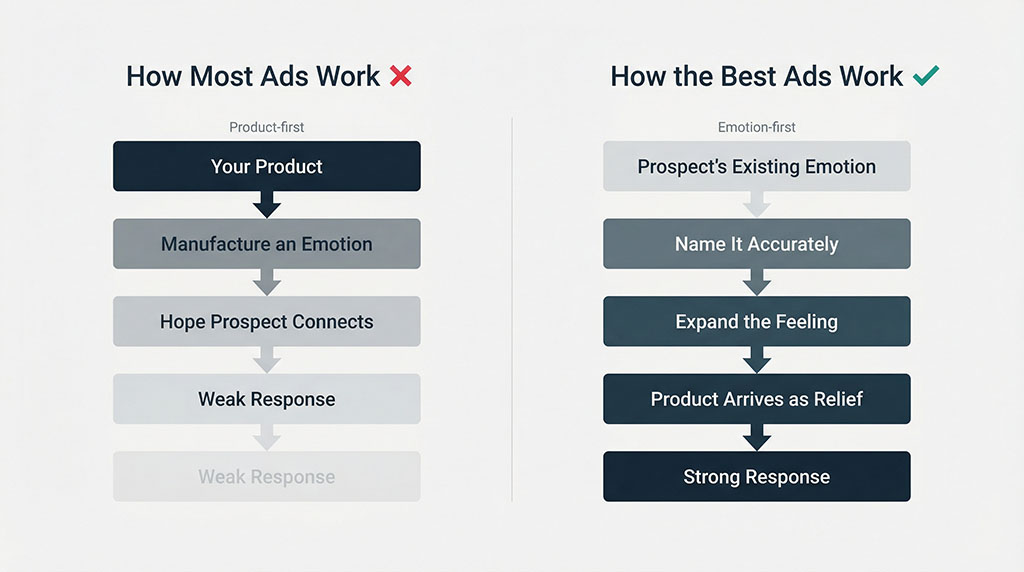

Copywriter Clayton Makepeace called this the “dominant resident emotion” — the feeling your prospect is already carrying around before they ever see your ad. It’s not a reaction to your copy. It’s a pre-existing condition.

Think about that for a second. Your prospect isn’t a blank slate waiting to be moved. They’re already angry, or scared, or frustrated, or embarrassed. They’ve been living with this feeling — sometimes for months, sometimes for years. It colours how they see your industry, your competitors, your promises. It shapes what they believe is possible and what they’ve given up on.

Your job isn’t to create a feeling. Your job is to name the one they already have.

When you do this well, the effect is visceral. The prospect reads your headline and thinks, “How do they know?” They feel seen. That feeling of being understood — of someone articulating the thing they’ve been struggling to put into words — is more persuasive than any benefit stack you could write.

Here’s what that looks like in practice.

Three ads that found the dominant resident emotion

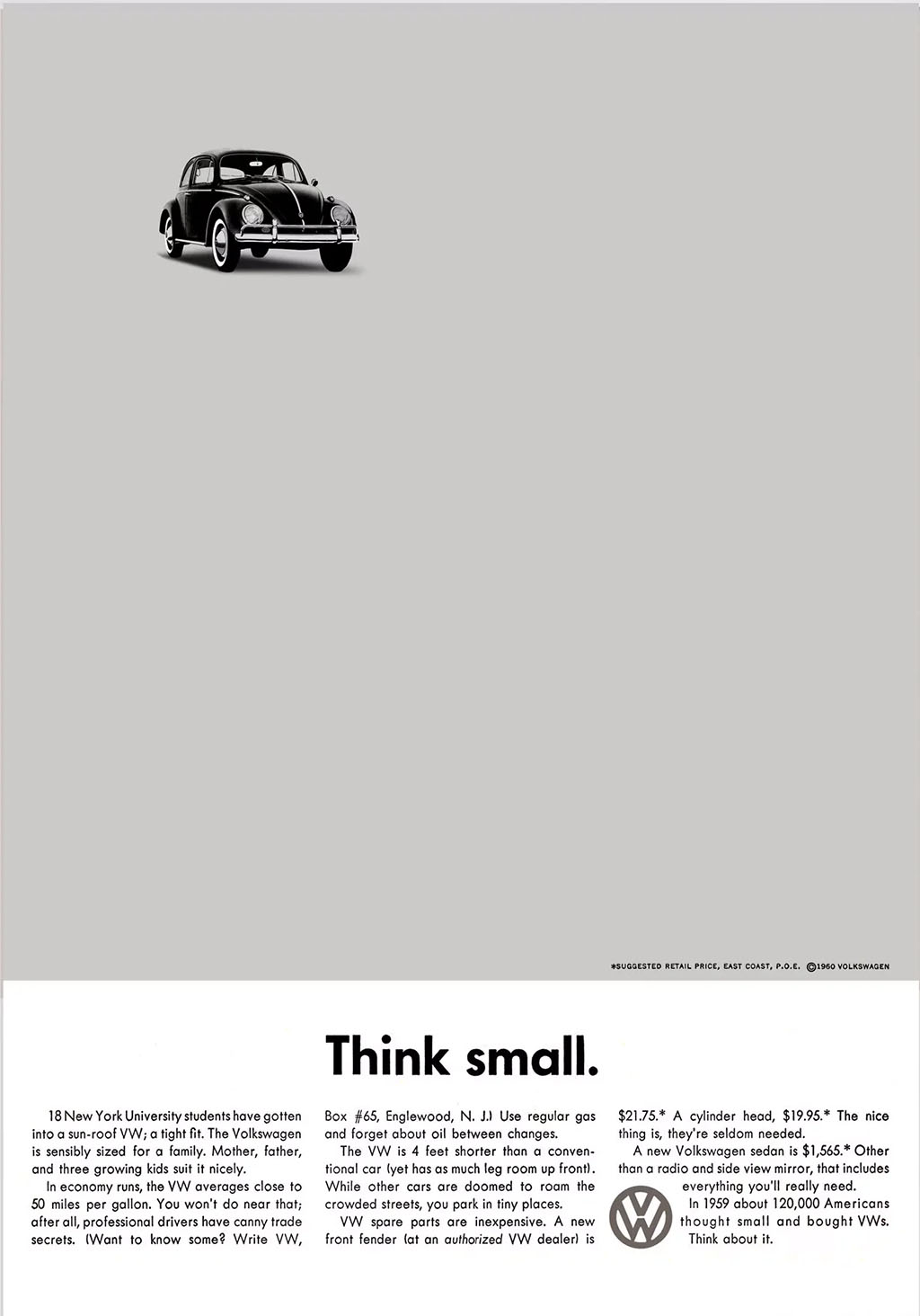

Volkswagen “Think Small” (1959)

In the late 1950s, American car ads were loud. Chrome. Fins. Bigger, faster, more powerful. Every manufacturer screamed superiority.

The dominant resident emotion of a growing segment of buyers? Exhaustion. Skepticism. The sneaking feeling they were being conned by an industry that made cars obsolete every two years to force another purchase. They didn’t want bigger. They wanted to stop being lied to.

Volkswagen’s agency, DDB, didn’t try to generate excitement about a small, ugly, German car. They connected to the fatigue. “Think Small.” A tiny car in a sea of white space, surrounded by ads screaming at maximum volume. The ad whispered. And the audience — already tired of being yelled at — leaned in.

The campaign ran for over a decade and turned a car with every rational disadvantage into a cultural icon.

Dollar Shave Club launch video (2012)

The razor market was dominated by Gillette. Their ads featured athletes, precision engineering, laboratory close-ups of blade technology. Feature after feature after feature.

The dominant resident emotion? Rage. Quiet, simmering, specific rage — at paying $6 per cartridge for a product that hadn’t meaningfully changed in years. Every man standing in a drugstore aisle, staring at locked razor cases, felt it. They felt ripped off and vaguely insulted.

Dollar Shave Club’s launch video didn’t open with product benefits. It opened with the emotion: “Are you paying too much for razors?” The rest of the video channelled that specific frustration — irreverent, funny, and pointed. Not because humour “sells,” but because humour was the natural expression of that particular anger.

The video hit 12,000 orders in the first 48 hours. Not because the razors were better. Because someone finally said the thing buyers had been feeling for years.

Apple “Think Different” (1997)

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple, the company was 90 days from bankruptcy. The conventional play would have been to advertise product specs. Prove the machines were competitive.

The dominant resident emotion of Apple’s core audience wasn’t about computers at all. It was about identity. These were people who had always felt slightly out of step — creative misfits who chose the “wrong” platform and took grief for it from the Windows majority. They felt like outsiders.

“Think Different” didn’t mention a single product. It connected to that feeling of not fitting in — and reframed it as a badge of honour. The crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. Apple didn’t ask people to evaluate a computer. They asked people to recognise themselves.

The campaign didn’t sell machines. It sold belonging. Revenue doubled in the following year.

"But this doesn't apply to my business"

Right about now, you’re likely thinking some version of this: That’s fine for Volkswagen and Apple. They have massive budgets and creative agencies. I’m selling accounting software. Or dental services. Or B2B logistics. My customers are logical. They compare features and prices. They make rational decisions.

That objection feels airtight. And Damasio’s patients felt perfectly rational too — right up until they couldn’t choose between chicken and turkey.

Your B2B buyer sitting in a procurement meeting? They’re afraid of making a recommendation that fails publicly. That’s fear of professional humiliation — a dominant resident emotion.

Your dental patient comparing prices on Google? They’re embarrassed about how long they’ve let their teeth go. That’s shame — a dominant resident emotion.

Your accounting software prospect downloading comparison spreadsheets? They’re terrified of their current system breaking during tax season and them being the person who didn’t fix it in time. That’s anxiety about competence — a dominant resident emotion.

The emotions are different from consumer brands. They’re quieter. More professional. Often unspoken. But they’re running the decision just the same.

The question isn’t whether your prospects buy on emotion. They do. The question is whether you know which emotion.

How to find your prospect's dominant resident emotion

This isn’t something you can guess from a brainstorming session. You find it by listening — specifically, by listening for the language your prospects use when they think nobody’s selling to them.

Mine your customer conversations. Not the polished testimonial. The offhand comment during onboarding. The frustrated aside in a support ticket. The thing they said in the sales call before they caught themselves being too honest. That’s where the real emotion lives.

Read reviews — yours and your competitors’. Not for feature feedback. For emotional leakage. The one-star review that says “I felt stupid trying to set this up” tells you more about what to write than any five-star review ever will. The emotion embedded in that review — the embarrassment of feeling incompetent — is a dominant resident emotion shared by thousands of prospects who never wrote a review.

Ask the question nobody asks. Not “Why did you buy?” — that triggers rationalisation. Instead: “What was happening in your business the week before you started looking for a solution?” That question bypasses the logical justification and surfaces the emotional catalyst. Something was going wrong. Something felt bad. Something became unbearable. That’s the emotion your ad needs to speak to.

You’re looking for the specific, concrete feeling — not a category. “Fear” is too broad. “Fear that my boss will ask about the campaign results and I won’t have an answer” — that’s a dominant resident emotion you can write to.

Writing the ad: emotion first, product second

Once you’ve identified the dominant resident emotion, the structure of your ad inverts. Instead of leading with your product and hoping to create a feeling, you lead with the feeling and let the product arrive as relief.

Open with recognition, not claims. Name the emotional state your prospect is living in. Not with clinical detachment — “Many business owners experience stress” — but with the specific, textured language they’d use themselves. “It’s Sunday night and you’re already dreading Monday’s inbox” hits different than “reduce workplace stress.”

Expand the emotional reality before offering the solution. This is where most marketers panic. They name the emotion and immediately rush to the product because sitting in the discomfort feels risky. Don’t rush it. Let the prospect feel understood for a few more sentences. The longer you accurately describe their reality, the more authority you earn to prescribe the solution.

Introduce the product as the resolution of that specific emotion. Not “our software has 47 features.” Instead: “So you stop waking up at 3 AM wondering if the numbers are right.” The product is framed as the end of the feeling — not as a collection of specifications.

This is what Ben Settle means when he says the best copy creates a vision of the problem, expands it, makes it vivid — then introduces the solution. Most ads do the reverse. They lead with the solution to a problem the prospect hasn’t been given space to feel yet.

The emotion checklist you actually need

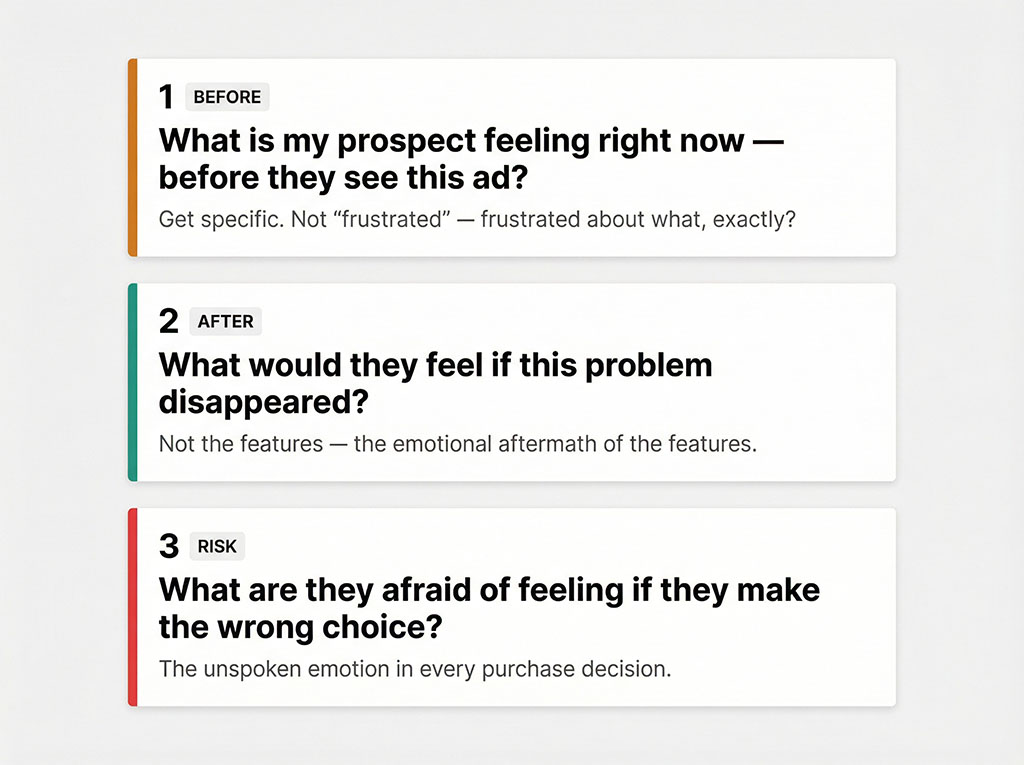

Forget generic lists of “22 reasons people buy.” Those are reference material, not tools. When you’re writing an ad, you need to answer three questions:

What is my prospect feeling right now — before they see this ad? Get specific. Not “frustrated” but “frustrated because they’ve tried two other tools that promised to be easy and both required a developer to set up.” The specificity is the persuasion.

What would they feel if this problem disappeared? This is your bridge to the product. Not the features — the emotional aftermath of the features. Relief. Confidence. Pride. Control. “I finally don’t have to apologise for our reporting” is more motivating than “real-time analytics dashboard.”

What are they afraid of feeling if they make the wrong choice? This is the unspoken emotion in every purchase decision. The fear of buyer’s remorse. The fear of looking foolish for switching systems. The fear of spending money and getting the same result. Address this emotion directly — usually in your guarantee, your social proof, or your risk-reversal — and you remove the last barrier between desire and action.

The $40,000 ad, revisited

That ad from the opening — the one with the studio shots and the soaring soundtrack and the $65,000 total spend? The product was a project management tool for small agencies.

The dominant resident emotion of small agency owners isn’t aspiration. It’s not “I want to be more productive.” It’s dread. It’s the specific, stomach-tightening dread of Sunday evening, knowing that Monday will bring the same chaos — the same missed deadlines, the same client emails asking for updates that require 30 minutes of digging to answer, the same feeling that the business is running them instead of the other way around.

The ad that finally worked didn’t have a single product screenshot. It opened with six words: “It’s Sunday night. You’re already stressed.”

Click-through rate tripled. Cost per acquisition dropped 60%. Not because the product changed. Because the ad stopped performing emotion at people — and started naming the one they were already carrying.

Your prospects already feel something. Your ad just needs to find it.

Find the Emotion Your Ads Are Missing

We’ll audit your current ad copy against your prospect’s dominant resident emotion — and show you exactly where you’re performing feelings instead of connecting to them.

Most clients discover their ads are leading with product benefits while the emotion that actually drives the purchase decision goes completely unaddressed. Takes 30 minutes.

You don’t need better creative. You need to say the thing your prospect already feels.