The quarterly content report landed with a thud. Forty-seven slides. Impressions up 340%. Engagement rate: “industry-leading.” Blog traffic doubled. The agency beamed through the screen like they’d just cured something.

The business owner sat quiet for a beat. Then asked the only question that mattered.

“How many of these people bought something?”

Silence. The kind that costs $8,000 a month.

Here’s what nobody in the content marketing industry wants you to think about too carefully: producing content that doesn’t ask for the sale is the safest job in marketing. You can’t fail at it. There’s no rejection. No awkward conversion rate staring back at you. Just a steady stream of blog posts, carousels, and “thought leadership” pieces that look busy, feel productive, and never have to prove they made the phone ring.

Drayton Bird — the man David Ogilvy called the best direct marketing copywriter in the world — spent decades watching this unfold. His diagnosis is blunt: “content” is just long copy without the bit asking for a sale, because allegedly people don’t like to be sold to.

That “allegedly” is doing a lot of heavy lifting.

The comfortable lie agencies sell themselves

The whole premise of content-as-strategy rests on a single assumption: people hate being sold to. Bird calls this what it is. B.S. People don’t hate being sold to. They hate bad salespeople. They hate lazy pitches, irrelevant offers, and the feeling of being a number on someone’s pipeline report. But a genuinely helpful, well-timed, well-crafted sales message? People welcome that. Think about the last time a friend recommended something you actually needed. That felt great. That was selling.

He’s not alone in this. Raymond Rubicam, who built Young & Rubicam into one of the world’s largest agencies, put it plainly: the aim of advertising is to sell — it has no other function worth mentioning. John Caples, the man who wrote some of the most tested direct-response ads in history, said something even more useful: when people have read your copy, they want to know what to do. Tell them.

Three legends. Same message. And yet most agencies in 2026 are still producing content that does everything except ask for the sale.

The reason is uncomfortable but simple. Any competent writer can produce content. You brief them on a topic, they research for an hour, and something publishable comes out the other end. It fills a content calendar. It generates a metric. It justifies a retainer.

But making someone reach for their wallet? That requires understanding the customer’s specific pain, the exact moment they’re ready to act, and the precise words that move them from interested to committed. That’s hard. That’s risky. And when it doesn’t work, there’s nowhere to hide.

Content without a sales objective is the agency equivalent of looking busy at your desk. The screen’s on. The keyboard’s clicking. But nothing’s shipping.

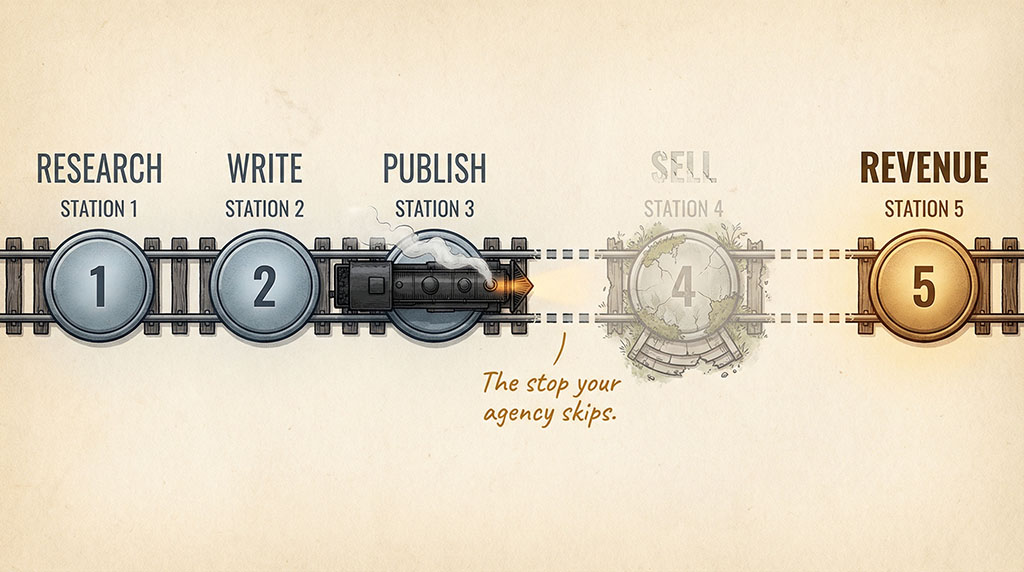

The train that stops one station early

Bird has an analogy that should be tattooed on every agency’s pitch deck: running copy that doesn’t sell is like catching a train from London to Edinburgh and getting off the stop before your destination.

You did 95% of the work. You researched the audience. You crafted the headline. You wrote something genuinely useful. And then — right at the moment where all that effort could convert into revenue — you stopped. You published it with a vague “follow us for more” and moved on to the next piece.

Why? Because that last 5% — the clear, confident ask for the sale — is the part that gets measured. And measurement is the natural enemy of agencies billing for activity rather than outcomes.

"But content marketing generates 3x more leads per dollar"

Here’s where the sceptical reader pushes back — and they should.

You’ve seen the stat. Content marketing costs 62% less than traditional marketing and generates roughly three times as many leads. That’s from Demand Metric, and it’s been recited so often at marketing conferences it’s practically scripture. HubSpot built an empire on the inbound methodology. Every SaaS company on earth runs a blog. Are you seriously saying all of that is wrong?

No. The concept of helpful content isn’t wrong. What’s wrong is calling it a strategy when there’s no commercial architecture underneath it.

Here’s the difference nobody talks about: the companies where content marketing actually works — the ones generating those impressive ROI numbers — aren’t just “creating content.” They’ve built strategic systems. They know exactly which business objective each piece serves. They’ve mapped their audience’s pain points to specific stages of a buying cycle. They’ve chosen platforms based on where those buyers actually spend time, not where the agency has a template ready to go. And they measure whether the content moved someone closer to a purchase — not whether it got a like.

That’s not content marketing. That’s a sales system that happens to use content as its medium.

The businesses where content marketing fails — which is most of them — are the ones where an agency produces 12 blog posts a month, schedules some social media, sends a report full of traffic numbers, and calls it strategy. There’s no connection between what gets published and what the business needs to sell. No audience architecture. No platform rationale. No measurement tied to revenue.

It’s activity disguised as strategy. And it costs a fortune.

What content looks like when it's built to sell

Bird’s definitive advice is six words long: make your copy helpful and likeable — then sell like hell.

The “sell like hell” part isn’t about being pushy. It’s about having a commercial purpose for every piece of content you produce — and the strategic backbone to make that purpose clear.

That backbone has three layers most agencies skip entirely.

Strategy first. Before a single word gets written, you need answers to foundational questions. What business objective does this content serve — lead generation, brand authority, direct sales? Who specifically are we trying to reach, and what’s the pain point that makes them care right now? Which platform puts this content in front of that person at the moment they’re most receptive? This is what frameworks like SOSTAC exist for — Situation, Objectives, Strategy, Tactics, Action, Control. Without this architecture, you’re not planning. You’re just filling a calendar.

Tactics with intent. Each piece of content needs a job description. Not “raise awareness” — that’s meaningless. Something measurable: drive enquiries from mid-market CFOs evaluating their agency spend. When the person writing the content is also the person accountable for whether it generated revenue, the content gets sharper. The call to action gets clearer. The fluff disappears. There’s no room for a 2,000-word blog post that could have been a 400-word email with a booking link.

Measurement that connects to money. Not impressions. Not engagement rate. Revenue attribution. Did the person who read this piece take the next step? At minimum, you should be able to trace the path from a published article to an enquiry. If your analytics can’t show you that journey, you’re measuring the wrong things — and your agency has no incentive to fix it, because vague metrics are easier to dress up in a slide deck.

Before your next content meeting, ask your agency one question: “Which specific business objective does each piece we’re publishing this month serve?” If they can’t answer without reaching for words like “awareness” or “engagement,” you’ve found your problem.

The real problem isn't content — it's fragmentation

Here’s where Bird’s critique connects to something bigger.

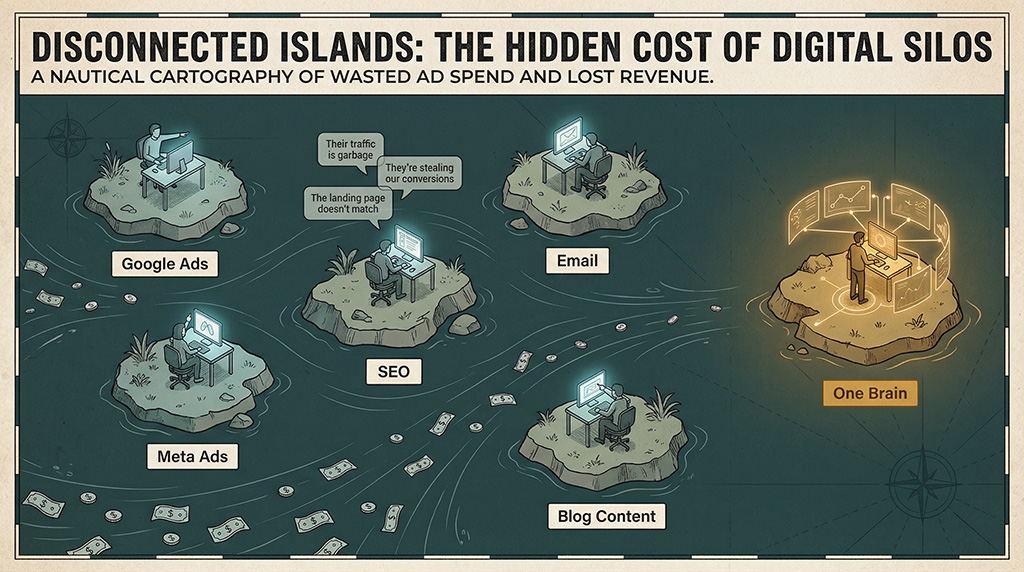

Most businesses don’t have one agency producing content. They have three, four, five — a Google Ads person, a Meta specialist, an SEO consultant, an email team, maybe a freelance copywriter for the blog. None of them talk to each other. None of them share data. And none of them are accountable for the full journey from first touch to sale.

I’ve sat in those meetings. The Google Ads person blaming Meta for stealing conversions. The email team saying the ad traffic is garbage. The landing page designer who hasn’t seen the ad creative. Everyone presenting their own metrics in their own format, nobody owning the outcome. After the fifth time you see this play out — same dysfunction, different company — you stop thinking it’s a coordination problem. It’s a structural one.

In that environment, “content strategy” becomes a convenient fiction. The social team produces posts that don’t reference what the ad team is running. The email sequences ignore what the blog just published. The SEO consultant optimises for traffic that the sales team can’t convert because the landing page doesn’t match the ad creative.

Everyone’s producing content. Nobody’s selling.

When you collapse that fragmented mess into one integrated system — one strategist who sees the whole picture, connects every channel to a single commercial objective, and measures the only metric that matters — content transforms. It stops being an agency’s busywork and starts being what Bird always wanted it to be: helpful, likeable copy that sells like hell.

Back in the conference room

Same quarterly meeting. Same business owner. Different report.

This one’s four pages, not forty-seven. It shows which content pieces generated enquiries. Which enquiries converted. What the customer acquisition cost was per channel. Where the funnel leaked and what got fixed.

The business owner looks at the numbers. Nods slowly.

Nobody in the room needs to ask whether people bought something. The report already answered it — because someone finally built the system to make content accountable for revenue, not just attention.

Bird would approve. Probably still grumble about something. But he’d approve.

See What Content Looks Like When It’s Built to Sell

We’ll map your current content output against a revenue-architected model — and show you exactly where effort is being spent without a commercial objective attached.

Most clients discover they’re producing 3–4x more content than they need — and none of it has a clear path to a sale. Takes 30 minutes.

Your agency doesn’t need a bigger content calendar. It needs a reason for every piece to exist.