The biggest hole in your AI strategy isn't the technology. It's the three-sentence Slack message you used to describe what you wanted.

A business owner walks into a meeting with their designer. The entire creative direction for their new campaign — the one that’s supposed to drive leads for the quarter — is a single sentence: “Make it pop.”

Not a joke. Not an exaggeration. Mark Duffy, writing in Digiday, catalogued real briefs from real businesses and called them “the worst pieces of communication in business history.” His collection reads like a comedy special: “JAZZ IT UP.” “Do something different but the same.” And the perennial classic — “I’ll know it when I see it.”

You’ve said some version of these. So has every business owner who’s ever hired a freelancer or agency. And until recently, it mostly worked out. Not because the brief was good — but because the person on the other end was experienced enough to fill in the gaps. They’d ask follow-up questions. They’d interpret. They’d present options and use your reaction to figure out what you actually meant.

That interpretation layer was doing the real work. The brief was broken, but nobody noticed because humans were quietly fixing it.

That layer is disappearing. And AI is what’s replacing it.

The problem you already have (that's about to get worse)

Let’s be honest about how briefs actually work in small businesses.

You’re running the operation. You’re across sales, fulfilment, staffing, and cash flow. Marketing is the thing you know matters but can never give the attention it deserves. So when you need a campaign, an ad, a landing page, or a batch of content, you fire off a message. It’s quick. It’s vague. It’s written between meetings or from the back seat of a car.

“Can you do something for our winter sale? Similar vibe to what [competitor] is doing but more us.”

“Need some social posts for the new service. You know the audience.”

“Just make it look professional.”

This isn’t laziness. It’s the reality of being a business owner with seventeen other fires burning. Ed Tsue, Chief Strategy Officer at Google/WPP, diagnosed the pattern across the entire industry: most briefs are regurgitated objectives from a conversation, vague audience definitions, and deadlines like “tomorrow.” Irish designers Mark Shanley and Paddy Treacy collected real client feedback and turned them into an art exhibition — because the absurdity was universal. “Can the snow look a little warmer?” “We feel red just isn’t right for Christmas.” Every creative on the planet recognised their own inbox.

The BetterBriefs Project — the largest global study on marketing briefs, surveying 1,731 professionals across 70 countries — found that three in five marketers admitted to using the creative process itself to figure out the strategy. Meaning the brief was so unclear they needed to produce actual work just to discover what was wanted. The study estimated a third of every marketing budget is wasted this way. For a small business spending $5,000 a month on marketing, that’s $20,000 a year set on fire because nobody spent 30 minutes defining what success looks like.

But here’s the thing — when production was slow and human-driven, you could absorb that waste. It was built into the timeline. The freelancer asked questions. You had a call. They showed you a first draft that was wrong, and the conversation around why it was wrong became the real brief. Three weeks and two revisions later, you had something decent.

That process — slow, messy, inefficient — was secretly a correction mechanism. The friction was a feature.

AI just removed the friction.

Faster, cheaper, and exponentially more wrong

Here’s what changed. AI has compressed content creation timelines by 70–95%. Blog posts that took 8–10 hours now take under two. Image generation delivers in seconds. An entire campaign’s worth of assets can be produced in an afternoon for the cost of a software subscription.

That’s the pitch, anyway. And the speed is real. 73% of marketing teams now use generative AI, nearly doubling from 37% in 2023. 93% of users report creating content faster. The cost of execution is approaching zero.

But the cost of direction hasn’t dropped at all. If anything, it’s spiked.

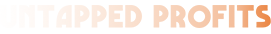

When you sent a vague brief to a human freelancer, the worst case was one wrong deliverable that took two weeks to produce. You’d see it, course-correct, and the next round would be closer. Slow and wasteful, but the blast radius was small.

When you feed that same vague brief into an AI-accelerated workflow, you get ten wrong deliverables in two days. A full campaign — social posts, ad variations, email sequences, landing page copy — all produced at speed, all consistently, confidently, and precisely wrong. Not wrong in an obvious way. Wrong in the way that looks professional but misses the audience, misframes the offer, or emphasises the wrong benefit. The kind of wrong you don’t catch until the campaign has been live for a fortnight and the leads aren’t converting.

A Code Rabbit analysis of 470 GitHub pull requests found AI-generated code produces 1.7 times more logic issues than human-written code. Not syntax errors — the code ran perfectly. It just did the wrong thing, because the specification was flawed. The marketing equivalent: a polished, on-brand campaign that targets the wrong pain point. It looks great. It doesn’t work. And because AI made it cheap to produce, you shipped it before anyone caught the problem.

A Workday global report from January 2026 found that while AI increases speed, nearly 40% of the value is lost to rework and misalignment. The time AI saves doesn’t go to higher-impact work — it gets consumed fixing outputs that shouldn’t have been produced. Forrester’s 2025 analysis was blunt: “AI doesn’t fix bad processes — it amplifies them.”

You didn’t save money. You spent less producing more of the wrong thing. The mistake is cheaper per unit but ten times bigger in total.

"But the whole point of AI is that I don't need to overthink this"

Stop here. Because this is the objection that kills small businesses.

The AI sales pitch — the one you see on every SaaS landing page and LinkedIn influencer’s feed — goes like this: AI handles the execution so you can focus on the big picture. Just give it a direction and iterate. Speed wins. Don’t overthink it.

It sounds right. It feels right. It matches the way you already work — fast, intuitive, directional. And it’s catastrophically wrong.

“Iterate fast” assumes you know what you’re iterating toward. Without a clear brief — a defined audience, a specific message, a measurable outcome — you’re not iterating. You’re wandering. Each round of AI output feels like progress because something got produced, but you’re circling a target you never defined.

The BetterIdeas Project, published in 2025, found the average creative idea now requires five rounds of development to reach sign-off — up from three rounds in 2007. Five rounds of rework. At AI speed, that’s five wrong campaigns shipped before lunch. Adobe/Workfront research confirms poor initial alignment forces 33% of projects into substantial rework. The PMI reports that 52% of projects experience scope creep, and those that do exceed their initial budgets by an average of 27%.

Harvard Business Review research from UC-Berkeley found employees using AI actually worked at a faster pace, took on broader scope, and extended into longer hours. The title of the paper: “AI Doesn’t Reduce Work — It Intensifies It.” The speed doesn’t free you up. It creates a faster rework loop that consumes the time you thought you were saving.

Here’s the uncomfortable maths for a small business: if you’re spending $3,000 a month on AI-assisted marketing and 40% of the value is lost to misalignment, that’s $14,400 a year — gone. Not because the tools are bad. Because the brief was a Slack message.

What a real brief actually looks like (it's simpler than you think)

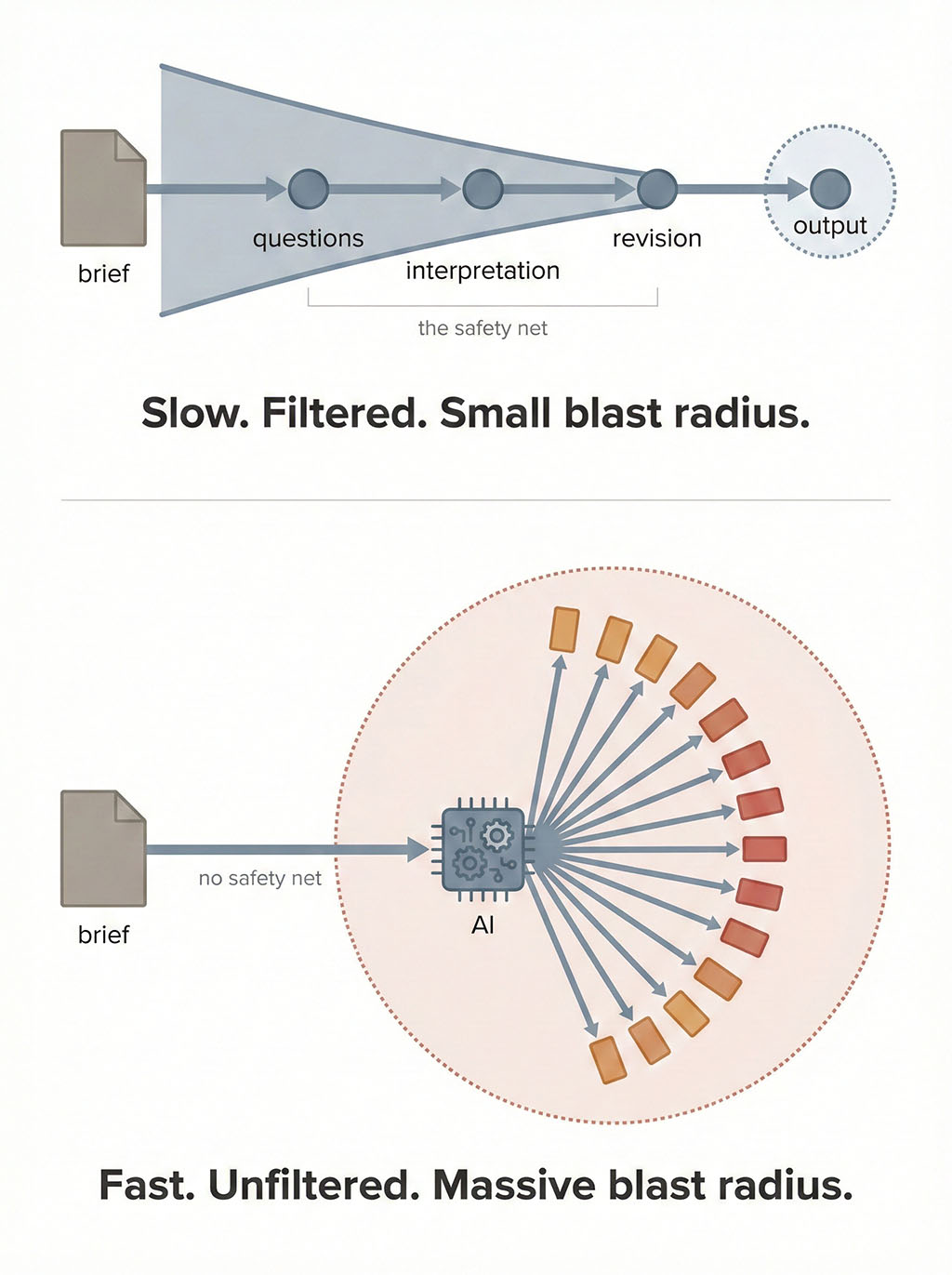

The fix isn’t a 20-page strategy document. Small businesses don’t need more process. They need sharper thinking compressed into fewer words.

Graham Robertson’s dissection of a “smart brief” versus a “bad brief” makes the gap visceral. The bad objective: “Drive trial, steal market share from competitors while getting current users to buy more often.” Three objectives fighting each other. The good objective: “Drive trial using the positioning of ‘The good tasting healthy cookie.'” One objective. One positioning.

The bad target audience: “18–65 years old, including current consumers, new consumers, and employees.” That’s everyone — which means it’s no one. The good target: “‘Proactive Preventers.’ Suburban working moms, 35–40, willing to do whatever it takes to stay healthy.” That’s a person. You can write for a person. You can’t write for “everyone aged 18–65.”

Richard Holman surveyed hundreds of professionals and found something telling: zero percent thought the briefs they received were too short. The problem is never too little information. It’s too much, with no hierarchy — no decision about what matters most.

But knowing what a good brief looks like in theory and actually writing one are different skills. So here’s the structure that closes the gap.

The five-part brief (the difference between a prompt and an assignment)

A prompt is a question. A brief is an assignment. The distinction sounds semantic. It isn’t.

A prompt says: “Help me with my emails.” A brief says: “Audit my 12-email welcome sequence stage by stage. Here’s the performance data — open rates, click rates, revenue per send, unsubscribes. Here are three emails that represent our best voice. Identify the three highest-impact changes I can make this week, and draft rewrites for the weakest performers.”

Same person. Same tool. Radically different output. The brief has five parts:

Context — What’s the business? What’s the product? Who’s the customer? What’s the price point? What’s working and what isn’t? The more context you provide, the less generic the output. This is the part most people skip entirely, and it’s the part that matters most. An AI with no context about your business will produce content that could belong to any business. That’s not a tool failure. It’s an input failure.

Objective — What do you actually need? Not “help me with marketing.” Something like “build a 30-day content calendar focused on driving trial signups, using only topic angles supported by our existing performance data.” Specific enough that you’d know whether the output hit or missed.

Constraints — What are the rules? “Match this brand voice.” “Don’t exceed 500 words per email.” “Focus on the welcome sequence only.” Constraints make output usable. Without them, the AI guesses — and it guesses wide.

Reference material — Upload examples of what “good” looks like. Your best-performing content. A competitor’s page you admire. A template you want to follow. This is the single biggest lever for quality. Software engineers solved this twenty years ago — they called it “acceptance criteria,” specific testable conditions that define “done” before any code gets written. Not “make it user-friendly.” Instead: “A new visitor can complete a purchase in under three clicks with no account creation required.” Your reference material serves the same function. It shows the AI what the finish line looks like.

Deliverable format — Tell it what you want back. A document? A spreadsheet? A list of rewrites with before-and-after comparisons? A prioritised action list ranked by estimated impact? Be specific about the shape of the output, and you’ll spend less time reformatting and more time refining.

That’s it. Five parts. You can write a brief in this format in 15–30 minutes. Less time than a single round of revisions on a bad deliverable.

What happens when the brief is actually good

This isn’t theoretical. Sam Woods, who writes the Bionic Business newsletter and gets early access to frontier AI models, recently documented what happened when his team used this exact approach on a real project — an email funnel audit they’d been putting off for weeks.

The funnel had a sales page, a 12-email welcome sequence, a five-email cart abandonment flow, three upsell sequences, and a win-back series. The kind of audit that normally takes two to three full days. Reading every email. Mapping the flow. Comparing performance data. Identifying weak links. Writing recommendations. Drafting rewrites.

Instead of prompting, his team briefed. They uploaded everything — the sales page, every email, the performance data export, the client’s brand voice guide, and three of their best-performing emails as style references. Then they wrote the brief: business context, what the product is, who it’s for, the price point, the sales cycle. They told it what they needed — a stage-by-stage audit with specific weaknesses called out by quoting exact lines, and rewrites they could implement that day. They told it to find patterns in the data — which hooks drive clicks, which CTAs drive revenue, which subject line structures get opens, and what the worst-performing emails have in common.

The output didn’t just “analyse” the funnel. It mapped the entire customer journey and found three disconnects that hadn’t been spotted in weeks of manual work:

The sales page was making a specific promise about “results in 14 days” that the onboarding sequence never mentioned again — for nine consecutive emails. The promise that got people to buy was completely abandoned the moment they became customers.

The highest-converting email hook in the welcome series — a customer transformation story — appeared exactly once and was never replicated. The thing that worked best was used the least.

The cart abandonment flow was using urgency language that directly contradicted the trust-building tone of the rest of the funnel. Two different voices in the same customer journey, pulling in opposite directions.

None of this was visible in any single email. It only becomes visible when something can read all 40+ pieces of content simultaneously and map the connections between them against actual performance data.

Two hours of total time. Ninety percent of that was reading and refining the output, not producing it.

That’s not a prompt getting lucky. That’s a brief doing its job. The context was rich enough and the objective specific enough that the output had nowhere generic to go. It was built from this client’s patterns, this client’s voice, this client’s data.

The distance between “help me with my emails” and that five-part brief is the distance between $14,400 a year in wasted marketing spend and a deliverable that a strategist would charge for.

The tools are already forcing the issue

Here’s the part that should make you pay attention even if you’re sceptical about briefing discipline: the AI tools themselves are starting to require it.

Anthropic recently released a plugin system for Claude that turns it from a generalist into a role-specific tool — sales, marketing, finance, legal. When you install the Sales plugin, the first thing it does is onboard you. It asks about your business: what you sell, who you sell to, what the typical sales cycle looks like, what your main value propositions are, what objections you hear most often.

It feels like onboarding a new hire. Which is exactly what it is.

Woods tested it with a real discovery call. He gave it a company name, a contact’s name and title, and their website URL. What came back was a five-page briefing document. It had pulled the company’s recent blog posts and analysed their content strategy. It had looked at their pricing page and mapped their positioning against competitors it identified on its own. It had found the prospect’s LinkedIn activity, pulled their job listings to infer what teams they were building, and cross-referenced all of it against the sales process he’d provided during setup.

The call prep that normally takes an hour happened in ninety seconds. And the output was more thorough than what he’d have produced manually, because it connected dots he wouldn’t have thought to look for — like the fact that the prospect was hiring three content writers, which signalled content velocity was a strategic priority.

But here’s the thing: none of that works without the ten minutes of setup context. Without the business description, the sales process, the value propositions, the common objections — the plugin produces the same generic output as any other AI query. The tool didn’t get smarter. The brief got richer.

The tools are moving in this direction because the companies building them have figured out the same thing this article is arguing: the bottleneck is not the model. It’s the user’s ability to provide context.

A marketing brief needs the same discipline. Not “make it engaging.” Instead: “Target owners of service businesses with 5–20 employees who are currently running Google Ads but not tracking conversions. One message: you’re paying for clicks that don’t become customers. CTA: book a free audit.”

That’s a brief an AI can execute correctly. It’s also a brief a freelancer can execute correctly. The difference is that the AI won’t ask you the clarifying questions the freelancer would — it’ll just produce something that fits the words you gave it. Which means the words have to be right the first time.

The strategist-implementer is the safest model in the room

This is where the real argument lands — and it’s not about writing better briefs. It’s about who holds the strategy.

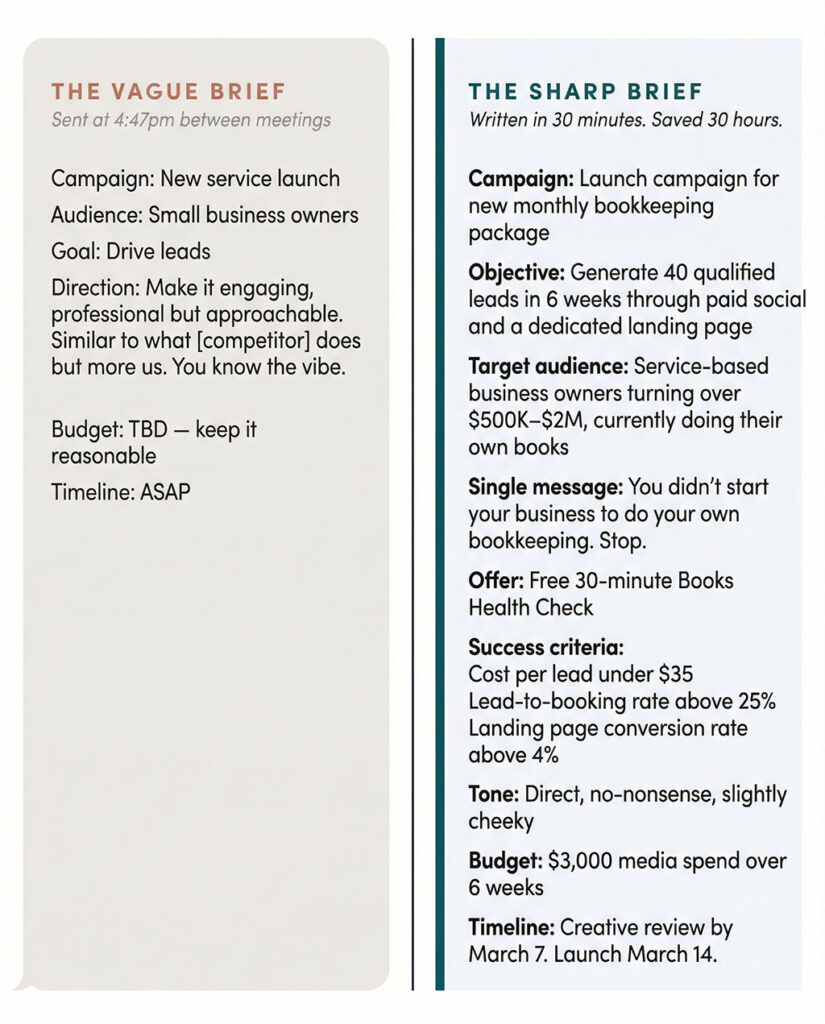

The traditional model works like a game of telephone. Business owner has a vision → writes a brief (badly) → sends it to an agency or freelancer → they interpret it → produce work → business owner reacts → rework begins. Every handoff is a point of failure. Every translation loses signal. The brief is the weakest link in a chain with too many links.

AI makes every link in that chain faster. But it doesn’t fix the chain. It just means you get to the wrong answer sooner. And the tools that are starting to require proper briefing — the ones that onboard you like a new hire before they’ll produce anything — are proving the same point from the other direction. The model works when one brain holds the full picture.

The model that survives this shift is the one with the fewest handoffs. Where the person doing the strategic thinking — defining the audience, the message, the success criteria — is the same person directing the execution, reviewing the output, reading the analytics, and adjusting in real time. One brain holding the whole picture. No translation. No telephone game. No brief lost in transit.

This is what the software world figured out: Amazon’s engineering environment forces developers to write a testable specification before any code is generated. Not because they don’t trust the developers — because they know the specification is the product. The code just expresses it.

Marketing works the same way now. The brief is the campaign. The strategy is the deliverable. And the person who can hold both — who understands the business well enough to define the target and skilled enough to build the funnel, write the copy, launch the ads, and read the data — that person is doing the highest-leverage work in marketing.

Everyone else is playing telephone. Faster.

The three-sentence Slack message, revisited

“Can you do something for our winter sale? Similar vibe to what [competitor] is doing but more us.”

That brief used to cost you two extra rounds of revisions and a frustrated freelancer. Now it costs you a full campaign — ads, emails, social, landing pages — all built at speed, all missing the mark, all live before you’ve had time to catch the problem. The tools got faster. The brief didn’t get better. And the gap between those two things is where your budget goes to die.

AI didn’t make the brief less important. It made the brief the only thing that matters.

The question isn’t whether you can afford to spend 30 minutes writing a proper one. It’s whether you can afford not to — or whether you need to find the person who can hold that thinking for you. Someone who doesn’t need a brief translated, because they’re close enough to the business to write it themselves. One brain. The whole picture. No signal lost.

That’s not a luxury. In an AI-accelerated world, it’s the minimum viable strategy.

Find Out What Your Brief Is Actually Costing You

We’ll review your current marketing setup — who’s doing what, how work gets briefed, and where the gaps between strategy and execution are bleeding budget. Most business owners find the rework cycle alone is costing them more than the campaign.

[Book Your Review →]

Takes 15 minutes. No pitch deck. No “let’s circle back.” Just a clear picture of where signal is getting lost between what you want and what’s being produced — and what one brain holding the whole picture would change.