Twelve records for a penny. That was the offer. If you grew up anywhere near a letterbox in the seventies or eighties, you remember the Columbia House mailer—that oversized card with the tiny perforated stamps you’d lick and stick next to the albums you wanted. Twelve records, one cent, and somewhere in the fine print, a clause that said they’d keep sending you records every month and billing your account until you filled out a cancellation form and mailed it back.

It smelled like cheap ink and possibility. It was also—and I didn’t know this for another thirty years—the exact business model that would power Netflix, Spotify, and every SaaS platform you’re paying for right now.

The subscription model your agency sells as "modern" is older than your parents

That Columbia House mailer was running what the direct mail industry called a “negative option” continuity programme. The consumer opts in once. The company keeps shipping and billing automatically. The friction required to cancel—finding the form, filling it out, posting it, waiting for confirmation—ensures a predictable baseline of recurring revenue, even from people who stopped caring months ago.

Sound familiar? It should. That’s the blueprint underneath every “subscribe and save” e-commerce model, every SaaS annual plan with an auto-renew buried in the terms, every streaming service that keeps charging you for a free trial you forgot to cancel. The billing runs through Stripe instead of a postal clerk, but the psychology is identical: human inertia is the most reliable revenue engine ever invented.

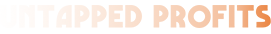

The direct mail pioneers didn’t stumble onto this by accident. They ran the numbers obsessively. They knew—decades before any venture capitalist coined the term—that acquiring a new customer costs five to seven times more than keeping an existing one buying. Sears, Roebuck and Co. built one of the largest retail empires in history on this principle. Their catalogues cost a fortune to print and distribute to rural addresses across the country. So they priced the front-end transaction to break even—sometimes to lose money—knowing the real profit came from every subsequent purchase that customer made over months and years.

The digital marketing industry calls this Customer Lifetime Value versus Customer Acquisition Cost. The mail-order industry just called it “backend selling.” Same maths. Same strategy. Different spreadsheet.

Your funnel was designed in 1966

I sat in a pitch meeting last year where an agency spent forty minutes walking a client through their “proprietary content framework.” Awareness content at the top. Consideration content in the middle. Conversion content at the bottom. Beautiful deck. Custom graphics. They even had a name for it—something with “Matrix” in the title.

It was Eugene Schwartz’s awareness model from 1966. Word for word.

Schwartz was a copywriter, not a tech founder. His book Breakthrough Advertising laid out five stages of customer awareness: Unaware, Problem Aware, Solution Aware, Product Aware, and Most Aware. His argument was sharp: you can’t create desire. You can only channel desire that already exists. The only way to do that is to match your message to where the customer sits on that awareness scale.

Someone who doesn’t know they have a problem needs a story, not a sales pitch. Someone comparing solutions needs proof. Someone ready to buy just needs the offer and a reason to act now.

That’s your marketing funnel. That’s what agencies call ToFu, MoFu, and BoFu. Schwartz mapped it out for print advertising nearly sixty years ago—and the framework hasn’t been improved upon since, because the psychology it’s built on hasn’t changed since.

Your top-of-funnel viral videos and quizzes? Those target Schwartz’s “Unaware” stage. Your SEO articles and comparison guides? “Solution Aware.” Your retargeting ads and urgency-driven email sequences? “Most Aware.” The digital tools accelerated the delivery. The thinking was done before the moon landing.

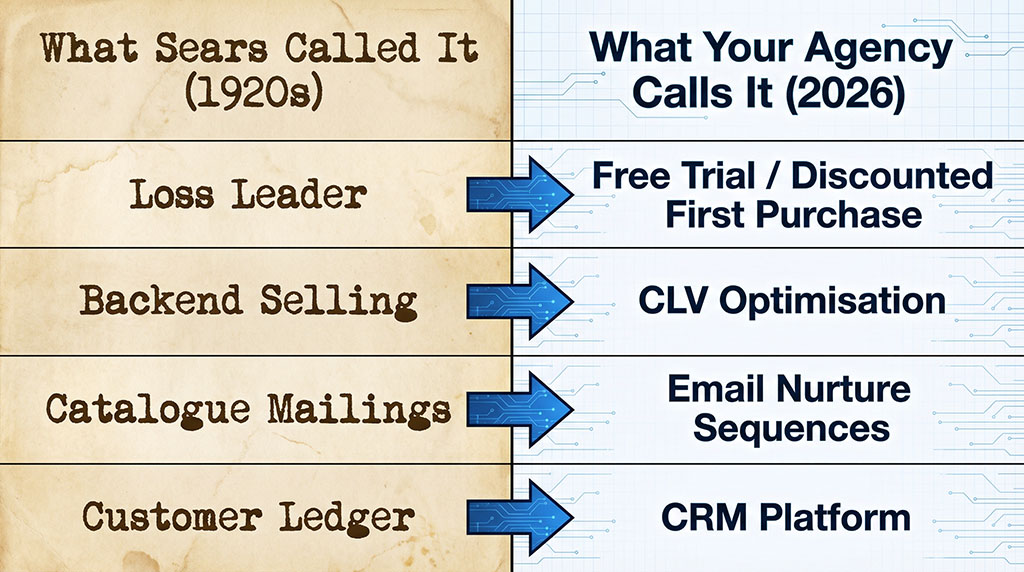

The exit-intent popup was a folded piece of paper

Here’s one that should bother you, because it shows just how granular the translation is.

In a traditional direct mail package—the kind a company would send to sell you a magazine subscription or a set of encyclopaedias—there was a standard collection of pieces: the main sales letter (long, persuasive, story-driven), a glossy brochure, and an order form. But the smartest direct mailers would include one more thing. A smaller, separate slip of paper, often folded in half so you’d have to open it like a note passed in class, with a provocative line printed on the outside: “Read this only if you’ve decided not to buy.”

They called it a “lift letter.” Its entire purpose was to catch the person who’d read everything, almost said yes, and was about to throw the whole package in the bin. The lift letter would address their final objection—restate the guarantee, add a personal endorsement, throw in one more reason to act. Its job was to “lift” the response rate by a few percentage points. On a mailing of a million pieces, that lift was worth a fortune.

Now think about what happens when you move your cursor toward the close button on a website. A box appears. “Wait—before you go…” It offers you a discount. It restates the guarantee. It addresses the objection you were thinking but never articulated.

That’s an exit-intent popup. It’s a lift letter. Same psychology, same placement in the decision sequence, same tactical purpose. The direct mail version detected hesitation by physical behaviour (the package sitting unopened for days, then finally being sorted into the “no” pile). The digital version detects it by cursor trajectory. The intervention hasn’t changed. Only the detection method has.

Cart abandonment emails work the same way. You add something to your cart, you leave without buying, and an automated sequence follows up—addressing objections, restating the offer, sometimes sweetening the deal. A lift letter delivered to your inbox instead of tucked inside an envelope.

Even the “Johnson Box”—that bordered, bold text at the top of a direct mail letter highlighting the core benefit before the salutation—has a digital twin. It’s the pre-header text in your email marketing software. One job: hook the reader before they’ve committed to reading the full message.

"But the technology IS the advantage"

This is where I lose a certain kind of reader. Usually the one whose agency bills by the hour.

The objection goes like this: Sure, the concepts might be old, but we’re operating in a completely different world now. Machine learning. Real-time bidding. Algorithmic optimisation. Multi-touch attribution. You can’t compare someone sorting index cards in a warehouse to what a modern ad platform does with a million data points per second.

I agree. Partly.

The technology is extraordinary. Cloud computing, predictive analytics, and AI have made it possible to test, measure, and personalise at a speed and scale that would have been science fiction to a 1970s mail-order operator. Claude Hopkins—the man who invented A/B testing by placing different coupons in different regional newspapers and manually counting the returns—would weep at the precision of a modern conversion pixel.

But Hopkins would also recognise something: the decisions haven’t changed. Who do I target? What do I say to them? When do I follow up? How do I price the first purchase to maximise the value of the second, third, and tenth? How do I test one approach against another and scale the winner?

Those are the same questions Hopkins was asking in 1923. The same ones Schwartz was answering in 1966. The same ones Lester Wunderman was solving when he built the first customer databases on magnetic tape in the 1960s and 70s—tracking purchase histories, segmenting lists, and delivering personalised messages through the post long before anyone had heard the term “CRM.”

The technology accelerates the delivery. It doesn’t replace the thinking. And if your agency can’t explain why they’re running a retargeting sequence—not just how to set one up in the platform—they’re not strategists. They’re button-pushers. And button-pushing is being automated by the month.

Kickstarter is a dry test with better graphics

One more parallel, because this one carries legal weight.

In the mid-twentieth century, publishing companies faced a brutal problem: printing thousands of copies of a new encyclopaedia or book series without knowing if anyone would buy it. The capital risk was enormous. So they invented “dry testing”—they’d create and mail elaborate promotional materials for a product that didn’t exist yet. If enough people sent in orders, they’d proceed to manufacturing. If the test flopped, they’d refund the money and cancel the project.

The Federal Trade Commission regulated this heavily. If you were dry testing, you had to disclose that the product was “planned” and might never ship. Consumer protection didn’t care that the tactic was clever. It cared that the customer knew what they were getting into.

Today, this is the foundation of the lean startup methodology. Build a landing page. Collect email waitlists. Process pre-orders for software that hasn’t been coded yet. Kickstarter and Indiegogo operate almost entirely on this model—asking consumers to fund concepts, not finished goods.

And here’s the kicker: digital marketers running pre-order campaigns and MVP landing pages are still bound by the same FTC Mail Order Rule that governed those 1960s encyclopaedia dry tests. The medium shifted from printed brochures to internet landing pages. The law didn’t shift at all. The strategy didn’t shift at all. Only the speed changed.

What this means if you're writing cheques to multiple agencies

I didn’t write this as a history lesson. I wrote it because the pattern has a practical consequence that costs business owners real money.

When the fundamental architecture of digital marketing was established decades ago, the value an agency provides can’t be the framework. The frameworks are public knowledge. They’re in books that cost less than lunch. The value has to be in execution—the speed, precision, and integration of how those frameworks are applied across your specific channels, with your specific data, toward your specific commercial goals.

That’s the problem with paying five different agencies to run five different channels. None of them owns the system. Your Google Ads person doesn’t know what your email team is sending. Your Facebook buyer doesn’t see what’s happening on the landing page. Your SEO consultant is building content that competes with your paid strategy. Everyone’s running fragments of a system that was designed—sixty years ago—to work as a single, integrated machine.

Schwartz’s awareness model doesn’t work if the top of your funnel is managed by one agency, the middle by another, and the bottom by a freelancer who’s never spoken to either of them. The backend economics that made Sears profitable don’t work if nobody’s tracking what happens after the first sale because that’s “someone else’s department.”

The direct mail operators understood something that the modern agency model has conveniently forgotten: the system only works when one brain sees the whole picture. When one person—or one team—controls the message from the first touchpoint to the tenth purchase, every piece reinforces the next. When five separate vendors control five separate pieces, you don’t have a marketing system. You have expensive noise.

Twelve records for a penny

That Columbia House mailer is sitting in a landfill somewhere. The paper decomposed decades ago. But the architecture it ran on—acquire cheap, retain through inertia, profit on the backend, track everything, test everything, and treat the whole customer relationship as a single economic unit—is running on your phone right now. It’s in your Spotify subscription. Your Shopify store. Your agency’s retargeting campaign.

The only question is whether the people you’re paying to run it understand where it came from. Because if they don’t, they’re not selling you strategy. They’re selling you buttons.

See What Happens When One Brain Runs the Whole System

Most businesses are paying multiple agencies to run fragments of a machine that was designed to work as one. We’ll show you where the pieces are fighting each other—and what it looks like when they stop.

Takes 30 minutes. You’ll see exactly where your spend is going, where it’s leaking, and whether the thinking behind it is worth what you’re paying.

You don’t need more agencies. You need one brain that’s read the blueprints.